The Great Race of 1823

Following is the third of a three-part account of this race and the preparations leading up to it.

“The feeling of the South against the North was aggravated to almost fury!” New York City newspaper reporter.

By: Walter Lazary /// August, 2024 /// 9,490 Words

Part Three

The Great Race

Tuesday, May 27th, 1823, will always be remembered as one of American thoroughbred horseracing’s greatest days, the first time in history that the burgeoning sport would command the attention of so much of the nation. The anticipation and excitement of the great race, a once in a lifetime spectacle, was overwhelming, and not just in New York. Interest had peaked in many cities and towns throughout the eastern part of the country, and the magnetism of this historic event pulled people to the city from literally hundreds of miles away. Those who couldn’t attend would soon be able to read about it. News reporters from eastern and central America descended on the city, many representing the country’s largest newspapers, while the smaller papers would receive details of the event by wire service.

The city itself was bedlam. People began arriving on the weekend, small dribbles at first, but then they began to pour in like a raging river, approximately twenty thousand of them making the long and sometimes arduous journey from various areas throughout the South, North, and Mid-West. Hotels everywhere were jammed beyond capacity, with complete strangers sharing rooms. The many restaurants and cafes were packed inside, while outside, long lineups were waiting impatiently to get in. Bars and taverns were overflowing, and drinking was heavy. Side bets were brisk, and countless arguments raged back and forth. Often, fisticuffs broke out, and the police, fearing full-fledged donnybrooks, were called in to keep order. It seemed that the only thing that was talked about or even thought about was the great race, with hundreds of hotly contested arguments over which horse would win.

New York crowded with visiting racing fans.

As people flowed into the city from various parts of the country, they joined the horses from the South that had already arrived. Eight had traveled up from their southern headquarters fully a week before their scheduled races, and a few days later, another ten arrived and were stabled in the barns just south of the track. All were in training for what would be a busy week of racing with a one-mile heat race for three-year-olds scheduled for day one, the four-mile Great Race to be run on day two, a four-mile heat race open to all horses set for day three, an open three-mile heat race on day four, and a two-mile heat race open to all horses slated to close the meeting on day five.

On Monday, May 26th, the opening day of the Union Course meeting, five thousand people attended the races, many of them, particularly those from the South, gawking at the new dirt surface, the only one of its kind in the world and certainly a far cry from the lush turf courses that they were used to back home. In the sport in America today, horses specialize on the surface that they compete on, some being turf specialists, while others are best on dirt, but back then, no one gave it much thought.

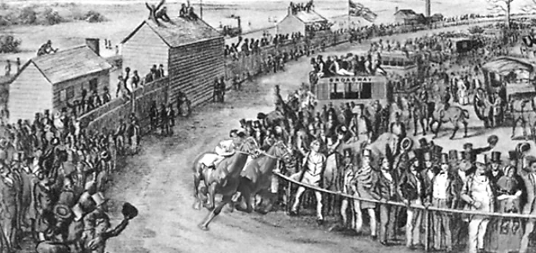

On Tuesday, the main crowd flowed out from the city, and it was monstrous. On every road, the mood was chaotic as huge throngs streamed to the track using every available road. It was reported in the New York Commercial Advertiser that seven thousand carriages made their way out to the track that day along with fifteen thousand single carriers and twenty thousand wagons. The police were being run ragged, either trying to direct traffic or monitoring the crowd, many of whom were boisterous. Northerners mixing with Southerners bordered on being a dangerous situation at the best of times, and the police constables were nervous. People were chirping back and forth, for most, good-naturedly, though not all. Many argued and got in each other’s faces, and often skirmishes broke out.

Crowds waiting to enter the Union Course.

With such a huge crowd, many people found themselves without a form of transportation, and those who could easily afford to rent a carriage found, to their dismay, that all were taken, and they were forced to walk out to the course. Long lines of carriages and buckboards stretched back for miles, joined by endless lines of walkers on each side of the roads laboring as the heat of the morning steadily built. And for those who chose not to come by land but across the bay instead, the ferries seemed to take forever and were packed beyond capacity, all carrying more people than the law permitted.

Josiah Quincy, Jr., who was just twenty-one years old and would eventually become the mayor of Boston, was unable to secure a ride in a carriage, but he was determined to get to the track even if he had to walk the nine-mile distance from Manhattan. “Every conveyance in the city was engaged,” he remarked. “Carriages of every description formed an unbroken line from the ferry to the ground. They were driven rapidly and in very close connection, so much so that when one of them had to stop suddenly, the poles from a dozen carriages behind broke through the panels of those preceding them.”

Josiah Quincy Jr.

Quincy eventually secured a ride, but when he got to the Union Course grounds, he was shocked at the huge crowds. “On arriving, we found an assembly that was overpowering,” he said. “It was estimated that there were more than one hundred thousand people on the ground.”

Outside the course grounds, hawkers pushing souvenirs were everywhere. Food venues were ringed with hungry, sweaty people, and the air was full of the tasty odors of barbeque food mixed in with the pungent scent of wood fire smoke. Lineups for food were long, and so was the entrance to the track. Inexperience in handling such crowds quickly became evident. Back in those days, there were no team sports. No one had heard of baseball or football or basketball or hockey. And there was no such thing as a concert. One of the most popular spectator sports was cockfighting, but even back then, a crowd of four hundred was considered huge. The Great Match Race would change all that, much as it already had in England, and the huge crowd that made its way out to the Union Course would be the first of many.

People buying food and souvenirs.

By noon, sixty thousand excited fans had jammed their way into the small grandstand and ringed the course along both the inner and outer rails. The grounds were so packed that a great many had to wait outside and never did see the race. On this historic day, The Great Match Race would be the largest attended spectacle of any sporting or non-sporting event in the country, and those sixty thousand people that swelled the Union Course were greater than the populations of all but three of America’s largest cities. This, of course, was a financial windfall for John Cox Stevens and the other owners of the Union Course. A sign stating the charges for entry onto the grounds was posted for everyone to see: Carriages were charged $1.50, Rigs $1.00, and Wagons 50 cents. Those who manned the carriages and those who wished to enter on foot were charged 50 cents each.

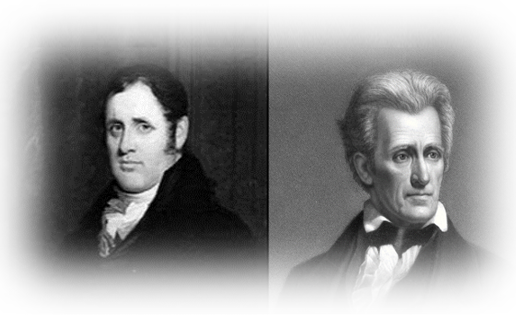

So enamored were people with this magnificent event that both the stock exchange and Congress were shut down for the day. And like every major event, even today, those with money and/or position had privilege. The social elite sat in the grandstand, their seating reserved under a sheltered roof, ensuring that they would be protected from the blazing sun. Dignitaries, politicians, financiers, and important business people were everywhere, chief among them Daniel Tomkins, the Vice President of the United States, and future President Andrew Jackson, at the time the Military Governor of Florida.

V.P. Daniel Tomkins and future President Andrew Jackson.

However, one prominent person would not be in attendance. William Ransom Johnson was stuck back in his hotel room, violently ill. He had contracted food poisoning the night before after eating lobster at a gala dinner arranged by Mr. Stevens, and try as he might, he couldn’t stop throwing up. His violent case of food poisoning would pass, but not in time for him to journey out to the track. His associate, Badger Bob, was now in charge, and carefully absorbing Johnson’s instructions, he headed out to Long Island, miraculously making it to the track on time.

The betting leading up to the race was fierce. Tens of thousands of dollars were wagered, much of it by fans betting against each other. They wagered both on single heats and on the race itself. But the wagering often went far beyond simple betting. Some put their future on the line as several Southerners risked large numbers of slaves and crops, and one, so confident that the South would at last show its racing superiority, bet his entire plantation on Henry.

Back then, just as it is now, weather was always a concern at big outdoor events, and it would be on this day too, though it wasn’t the threat of rain that was the problem. The skies were clear and the day sunny and it was extremely hot. It was the kind of day that should be spent at the beach and not at a racetrack as there was nary a breeze, the type of weather that we would call muggy and humid. People were sweaty and agitated, especially those who stood under the dreadfully hot sun without an umbrella to shade off piercing rays. Those with normally placid tempers were on edge, and it didn’t take much, usually just a single word, to start trouble. The police constables, themselves boiling hot, were aware of this, and whenever there was a confrontation they weren’t overly nice when breaking it up.

The crowd is ready and waiting for the horses.

As the morning slowly turned into afternoon and the big moment drew near, the crowd became even more agitated and testy. The Southerners couldn’t wait for Henry to show his tail to Eclipse and, once and for all, set the record straight. The Northerners smugly taunted them saying that the record already was straight. The arguing back and forth led to even more betting.

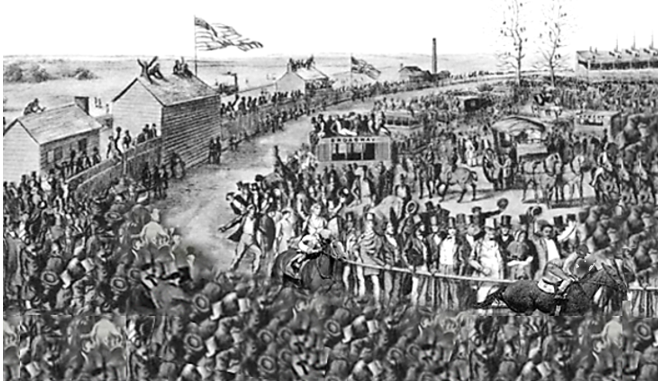

Finally, with the sun at its zenith and beating down mercilessly, it was time for the horses to make their entrance. The first to appear was Henry, and there was bedlam when he emerged from the crowd, his head swinging from side to side as he constantly searched his surroundings, his steps careful and his cautious manner much like that of a timid animal when it is drawn into an unsure situation. His boisterous supporters let out a loud cheer when he moved into view and then cheered even louder when the northern supporters tried to drown them out.

Southerners admiring Henry before the race.

The young colt had been in front of large crowds before, but nothing like this. He was already sweaty as he nervously paraded with his ears pricked straight up, his eyes wild and bewildered and white foam lathering around his mouth. He nickered and whinnied, and nervous sweat sheened across his shaky body. Clearly, he was unsure of himself, and Walden had to take a firm grip to keep him from suddenly bolting off.

Walden wanted to get Henry away from the main grandstand and most of the screaming and yelling, but as they moved along, he was forced to take up when their path was blocked by dozens of people who were out on the course making last-second wagers with each other. When an official asked them to clear out, some of them did, but most didn’t. This angered John Cox Stevens, and he stormed his way from his seat in the clubhouse down to the rail. He didn’t like what he was seeing and, for a brief second, contemplated bringing the police in to disperse the stubborn troublemakers. He thought better of it, however, and decided to order Walden to walk Henry right through them. Reluctantly the tiny jockey did, but it didn’t do much good. A few people scattered, but a rather large group still refused to budge.

With all eyes on Henry as Waldon moved him further down the track, suddenly the stares were shifting in a different direction. American Eclipse was about to make his entrance, and when he stepped onto the track the crowd erupted in a frenzied fever pitch that you could hear miles away. The great horse, his head bowed and his eyes fiery, pranced majestically like great champions always prance when they’re on parade and are aware that they’re the focus of everyone’s attention. He bounced past his admirers, his corded muscles bulging, snorting, and full of himself, his demeanor oozing the confidence of one who had been here before. And as he approached those who had remained on the course when Henry was paraded by, their arrogance gave way to awe, and they shrunk back. As if by magic, they dispersed, ducking under the rail so that all that remained were the two horses.

Ready to start the first heat.

Henry and Eclipse turned and paraded past the grandstand a second time and then pranced along the stretch toward the starting grid. The cheering was loud, but when they lined up ready for the start the cheers and the yelling and the taunting suddenly subsided, and it was ominously quiet. For many, the build-up leading to this great race had been long, and now, after all those months of waiting, the great race was just a few seconds from being underway. This strange quietude lasted for only a few seconds as a steady drum roll accompanied the horses when they slowly moved towards the starting line. Then the flag was lowered, and the two combatants were off, abruptly lunging forward as a loud roar rocked the grandstand and echoed off across the fields.

The First Heat

American Eclipse always ran his races while on the lead, a style that Van Ranst and the horse both felt comfortable with. The Old Wizard had been very explicit when he instructed Crafts to go to the front immediately and to do so without the least bit of hesitation. Johnson, however, was aware of the great horse’s running style and had ordered Badger Bob to instruct Walden to get Henry to the front as quickly as possible, no matter what the cost.

Walden was reluctant because he knew what Henry was like when he was in front early, but nevertheless, he did as he was instructed, and they shot away from the starting grid like a rocket. The crowd roared as Henry crossed over from the outside to the inside, and by the time they ran through the long straightaway and into that first turn for the first of four times, he had opened up a three-length lead.

The southern crowd was boisterous, roaring out chants of “Go Henry” when they saw their young upstart dash into the lead, and they roared even louder when he dug in. Running down the backstretch, Henry increased his lead to four lengths while Crafts was in a bit of a daze as he wondered what had happened. The young head-strong jockey had expected his horse to go to the front immediately on his own and didn’t push him at the break like Van Ranst had instructed him to. Stubborn to the point of being arrogant, and tired of listening to Van Ranst’s constant instructions, the young jockey, always smug, decided that he knew better anyway and would run the race his way.

When the lead had stretched out to five lengths, and Eclipse still failed to show signs that he could rally and cut into it, the great horse’s fans began to worry. Through the first two laps, Henry continued to set a fast pace, and he seemed to be doing it without a lot of effort. Several times, it appeared as if Eclipse was making a run, but each time, whatever ground he gained was quickly regained by the determined front-runner.

Trailing throughout the third lap, American Eclipse was now in unfamiliar territory. He was used to leading his races, not running second, and with the race on this new dirt course, he often hesitated when Henry’s churning hooves caused dirt to spray up with several large clods flying back and striking him in his face and eyes.

But the trouble that American Eclipse was experiencing on the track was of little consequence to his fans. What they were witnessing was unbelievable, and they looked on in utter shock and disbelief. Their hero was continuing to lag far behind. To them, this was something they never thought possible. The great horse had never lost a race, and in winning his seven previous starts, he had never even lost a heat.

When the two horses entered the final lap, Crafts’ arrogance evaporated, and he was now in panic mode. He realized that, try as he might, American Eclipse wasn’t gaining, and he suddenly started whipping and spurring. It appeared to work. Eclipse responded, and his cadence quickened, and with that, his stride lengthened as he began to cut into the margin. The crowd watched as the young horse’s lead was suddenly shrinking, dropping from five lengths to four and then down to three. Encouraged now that they were closing ground, Crafts continued to punish American Eclipse with the whip, if anything hitting the great horse even harder. The muscular smacks left welts and opened cuts on Eclipse’s side, and yet being the champion he was, the great horse ignored the bolts of pain and continued to dig in.

Turning into the stretch for that last frantic dash to the wire, Henry’s lead had dwindled down to a precarious two lengths, and American Eclipse, so hopelessly out of contention just one lap before, now suddenly looked like he might actually be able to pull it off. The crowd roared, the Northerners endeavoring to spurn American Eclipse on while the Southerners were imploring, almost begging Henry to keep himself together.

It was then that Crafts, instead of leaving well enough alone and letting the horse do his thing, decided that he still knew best. He let loose with another series of vicious whips, these so loud that the painful pops could be heard above the mighty roar that engulfed the small grandstand. The young, inexperienced jockey expected American Eclipse to dig in even more, but this time, something happened. Eclipse suddenly shuddered and threw his tail up and lifted his head. His ears were laid back and the muscles on his rear flanks that were bulging every time he drove forward had flattened out and sunk back against his frame.

A pall gripped the shocked northern crowd, and they gasped. The great horse, who just seconds before was making a furious drive, was now beginning to slow. It appeared that he had finally had enough of the whipping and abuse and was quitting. Enraged, Crafts hit American Eclipse even harder, but to no avail.

Up front, Henry was finally tiring and slowing himself, now totally spent after setting such a torrid pace. He had given his all and shuddered when he crashed headlong into that mythical wall that was there for every racehorse, his endurance waning and his speed shifting into a lower gear. But it didn’t matter. Henry might be running slower than American Eclipse, which allowed the great champion to close the gap, but American Eclipse was done and couldn’t dig in and take advantage. He had nothing left, and when they crossed the finish line, Henry had won the heat by less than a length.

Henry wins the first heat.

When Henry crossed the finish line, the atmosphere around the track was described as bedlam. Southern fans were ecstatic and threw up their hands and chanted, “Henry! Henry! Henry!” Their young horse had come, and he had conquered, just like the great trainer William Ransom Johnson, the man they called Napoleon of the Turf, said he would. The South was now in control and, after another heat, would once again be on top of the racing world.

And the time! When it was announced, it sent up yet another loud roar……..7m 37s, an American record.

With a half hour’s rest granted between heats, a despondent Van Ranst and his group realized the grave mistake he had made in replacing Samuel Purdy with Billy Crafts. It had been his decision, one that the others had frowned upon and tried to get him to change but to no avail. What was worse, Van Ranst finally realized just how good Henry was. The horse had run a magnificent race, and Ranst knew that of all the challengers that American Eclipse had faced in the past, Henry was a cut above, and yet he had only officially raced three times in his life.

Realizing that his horse would never win with Crafts aboard, a decision was made to approach the older veteran jockey Sam Purdy and ask him, even beg him if they had to, to ride American Eclipse. There had been harsh words between Van Ranst and Purdy when the jockey found out that he was being replaced. Probably any other time, he would have told Van Ranst what to do and wouldn’t have been nice about it, but deep down, his love for American Eclipse transcended any hard feelings that might have been percolating inside, and he agreed to ride.

American Eclipse, Van Ranst, and Purdy.

With his tack already on the grounds, Purdy approached American Eclipse and handed his saddle to a stable boy. The great horse was drenched as the stable boys ponged him down, trying to cool him off in the oppressive heat. The white foam that had gathered around his mouth had been washed away, and he was allowed to have a drink from a bucket. Purdy stood and tussled his mane and Eclipse nudged him with his nose and had a solemn look in his eye as if to say, “Where were you?” Purdy picked up on it and talked in a low, soothing voice, saying, “It’s all right, big fella. I’m here now.” Then he led the big horse out towards the track, and to the delight of the northern crowd, he was on Eclipse’s back when the second heat was about to begin.

The Second Heat

As time before the second heat dwindled down during the half-hour break, Henry, and not American Eclipse, was now the clear-cut favorite to win not only the heat but also the race, with many taking bets at odds of 3-1. This angered Purdy because he felt that if American Eclipse had benefited from a good ride, and not even a great one, he probably would have won the heat, but the smart-mouthed know-it-all Billy Crafts made sure that that didn’t happen. The abuse that American Eclipse had received at the hands of the young upstart had made Purdy even angrier, and he fanaticized taking Crafts out behind a woodshed and make him feel the sharp sting of a whip as it cut into his backside.

Enough, he thought, as the two horses made their way to the starting line. He knew he had to focus on the job at hand, that even the tiniest of mistakes could cause the great horse to lose the heat and, with that, the match. To cool his anger, he turned to the crowd and raised a hand to acknowledge his fans. The crowd erupted with a mighty roar, and yet as the cheering continued, its meaning changed. It was decidedly different from the cheering before the first heat when confident Northerners openly scoffed at and taunted the Southerners. Now, even with the presence of Purdy, they weren’t so confident anymore. Their cheering sounded desperate, nervous and with not a lot of hope. It contrasted with the boisterous cheers that slammed into them from the Southerners, who were brimming with confidence and were now outwardly mocking and taunting the Northerners.

Henry, even after a record-breaking performance, looked fresh, and he pawed at the ground, eager to get going. But American Eclipse had a different demeanor too. Most of the cuts on his flanks were superficial, and two deeper ones had been attended to and had stopped bleeding, but there had also been a cut on his testicles, and Purdy figured that that was the reason why the great horse had suddenly decided to quit.

As American Eclipse stood behind the starting line, his herculean reputation now in jeopardy, there could be no denying the fact that he had a deep affection for Purdy. He was suddenly calm again, and when looking into his eyes, one could see that he was eager. He trusted the old jockey, and theirs was that special kind of relationship where, if Purdy asked, this magnificent horse would lay it all on the line for him.

Standing beside them, Walden’s mind was racing through different scenarios. Henry had won the first race while leading all the way, but he tired badly at the end. If it was up to him, he wouldn’t break so fast in the second heat. He would stalk, conserve energy, and then make a dramatic charge and put the old horse away.

But orders were orders, and no one dared defy William Ransom Johnson. Because of the time it would take to travel back to the city, confer with Napoleon, and possibly change their strategy, no one traveled back, and they continued to follow the trainer’s original instructions.

Walden’s approach would be the same as in the first heat. Henry, who was on the inside this time, would break on top and get the lead which was where the young colt ran his best. If Eclipse wanted to go with him, he would have to use a large amount of energy to get by and cross over, and after that strenuous first heat, that’s exactly what Walden wanted, for the older horse to put out early and use up as much energy as possible.

Purdy, though, wasn’t stupid. He knew what to expect. Carefully watching the first heat, he could see that Henry had exceptional sprinting ability, and not just for a short distance. Johnson had trained his horses hard leading up to the big race, and they all had incredible foundations, but Henry’s ability to sprint all out for long distances came from within and wasn’t something that a trainer could train into a horse. Keeping this in mind, Purdy decided that rather than get into an early sprint battle, he would let Henry break on top and have his way. He would stalk patiently in behind and never let the southern horse get too far in front. Then, when the timing was right, he would make his move.

When they were finally off Henry broke from his inside post as fast as he did in the first heat. Walden, fully expecting American Eclipse to want the lead early, got into his horse right from the first jump, and by the time they made it through the stretch, he had opened up a three-length lead.

Walden was satisfied. The start went as he had planned, but where was American Eclipse? Looking behind him, the older horse was already out of sight and perhaps making a mistake; as they moved around the turn and into the backstretch, he encouraged Henry to continue to run at a much faster-than-normal pace. The horse did as he was asked, and the lead was increased to eight or nine lengths, which was greater than at any time in the first heat but superficial in Purdy’s mind after the young horse’s record time in the first race. He reasoned that the horse, any horse, only had so much to give, and no matter how impressive he was early on, that part of the race was only a memory. The only thing that mattered now was what was going to happen in the final lap.

American Eclipse’s fans didn’t have Purdy’s mindset, and even though they thought he was the best jockey in the world, they were still beginning to think that they were about to see a repeat of the first heat, that Henry would simply open up too much ground for Eclipse to catch him. Undaunted, Purdy kept to his game plan and, more importantly, kept American Eclipse in focus. When they rounded the next turn, Walden looked back and, seeing that Eclipse had dropped even further behind, began to think that Henry was going to win this race rather easily, maybe even in a romp.

American Eclipse was reputed to be the best racehorse in the country and, in many people’s eyes, maybe the best racehorse ever. He really was a true champion, and with Purdy, an old friend and a true champion himself, sitting on his back, even with Henry so far in front, the horse’s confidence was as great as it ever was.

The gallant warrior continued to gallop on, his heart waiting for a signal to pick up the pace, and when they began the second lap, the signal finally came. Purdy loosened the reins and asked the great horse to run – and that’s exactly what he did.

The northern crowd, their nervous buzz rolling across the grandstand and into the packed infield, suddenly came alive, and they began to cheer. American Eclipse was beginning to eat up ground. In fact, with every one of his long and powerful strides, he was devouring it so that by the time they entered the third lap, Henry’s lead was a little more than a length.

The northern crowd then watched intently as Purdy, the master strategist, went to work. He pulled the whip out from under his arm and cocked it, holding it up as a sign, a means of encouragement, and American Eclipse could see it out of the corner of his eye. He knew what Purdy’s intention was, and when the right moment came, he would be ready.

As they ran into the backstretch the country’s greatest ever jockey finally decided that it was time. He held the whip out again, though he wasn’t about to use it abusively like Crafts did. Instead of a prolonged series of whips, he gave the great horse just a single crack. A little further down the backstretch, he repeated the process. Then he put the whip away. American Eclipse got the message and, digging in, closed to within a half-length of the lead.

For the first time that day, Walden was worried. The confidence that both horse and rider had demonstrated throughout the afternoon had dissipated. Now he began to show signs of panic, and he pulled his whip out from under his arm and smacked Henry a couple of times. Ever obedient, which was something that he had rarely been known for in the past, Henry responded, and with American Eclipse chasing him under a full gallop, the race was on.

As both horses dug in and generated more speed, the cheering rolling down from the grandstand intensified. This is what the crowd wanted, indeed, expected, and they roared as the two combatants sprinted around the far turn and through the stretch with Henry still on the inside and Eclipse on the outside.

Entering the first turn for the final time, Henry was almost a length in front with Eclipse on his outside. It was at this point that Walden resorted to tactics of his own. He suddenly moved Henry out further from the rail, forcing Purdy to pull back so that Eclipse wouldn’t be pushed out too wide and lose even more ground. Now, American Eclipse was directly behind Henry, and as they moved through the turn, Purdy’s strategy was about to pay off.

What came next was a daring move that not only won the heat but might end up being the deciding factor as to which horse would win the race. Walden was off the rail, and Eclipse was directly behind him. Walden then made a fatal error. He looked over his right shoulder fully expecting Purdy to be driving Eclipse up alongside him. It was the one thing that Purdy was waiting for. There was barely enough room to drive Eclipse through on the inside, but that’s exactly what he did. The hole remained open, and when Walden once again looked back over his right shoulder, fully expecting Eclipse to be mounting yet another challenge, Purdy suddenly shot Eclipse through on the inside and gunned him into the lead.

Purdy makes a dramatic move inside.

The crowd roared when they realized that there was a new leader. The two horses, still in close quarters, swung off the turn and began their long run down the backstretch, American Eclipse with a short lead and a panicking Walden trying to get his wits back. Moving into the far turn, the lead was extended two lengths, and Walden went to the whip again. Henry tried to respond and gained a bit of ground, but when Purdy went to the whip one more time, Eclipse also responded.

The grandstand was rocking when the two horses turned into the stretch. Both riders knew that this was it – thoroughbred history was waiting to be made. If Henry got there first, he would forever be named America’s best, and the South would regain horse racing supremacy, a title that Purdy was not about to let slip away. The Northerners knew this too, and they roared out their encouragement.

Through the stretch they came, both jockeys now flailing away and encouraging their horses. Henry was continuing to gain an agonizing inch at a time, the crowd now delirious as it looked like he might get past the great champion. But Eclipse, being the champion that he was, sensed that he couldn’t let the younger horse get by – and he didn’t. Showing the resolve of a champion, he dug in, doing so without the need for the whip, and when they crossed the line, the race was suddenly tied. American Eclipse had won by a length.

American Eclipse wins the second heat.

With Henry losing the second heat after leading it for so long, and especially after his record-setting performance in the first heat, the young horse’s camp was shaken into a quandary. Not surprisingly, without Johnson’s cool demeanor and ever-present confidence, they began to panic. What they wanted to do most was talk to Johnson and get his instructions, but that was impossible with so little time between heats. Meetings and discussions took place as grooms calmed Henry and washed him down. Perhaps they needed a jockey change. From their position they really couldn’t see what happened on that first turn. The crowd was too thick, lined up along both the inside and outside rails. Little did they realize that the move that Purdy made on Walden would be talked about for ages. It was a move gripped with guts and determination, one where caution was thrown into the wind and that only a few jockeys in the entire world were capable of making.

Like most fans, they thought Purdy had passed Henry on the outside and that Walden showed his inferiority by allowing that to happen. With so many fans obstructing the view, it was impossible for many to tell which side Eclipse had passed on. When it was finally determined that the move had been to Henty’s inside, there was even more consternation, and even more blame was heaped on Walden. How could a jockey let a horse through on the inside?

Walden was beside himself. In actual fact, he had ridden an excellent race, keeping Henry together and not letting him run off in those first two laps. He still managed to keep the inside path in the turn all but closed off, with not enough room for most jockeys to even attempt to move a horse through. It wasn’t his fault that a suicidal move, one orchestrated by a masterful jockey, was what beat him.

If Johnson were present and not laying in a sick bed several miles away, he would no doubt have made the decision to stick with Walden. But he wasn’t present, and there was no time to have a rider race back and get his opinion. And so, the decision was made by a committee vote that Walden would be replaced and the jockey would be Arthur Taylor, himself a member of the group making the decision, a decision that he was not in favor of and had voted against. Taylor, who was now Johnson’s trusted assistant, was once a great southern jockey in his own right, but he had not ridden in several years. Nevertheless, the order was given, and Walden was officially replaced with Taylor.

Unlike after the first heat, when the two horses seemed eager to run again, as they were being prepared for the third heat their demeanor was dramatically different. Both were clearly exhausted. The hot sun was brutal, and with the barns being too far away for them to rest and get some much-needed shade before they lined up yet again, they remained standing in the open. Both were washed down, their mouths foamy and their eyes watery, their skin lathered with sweat, and their heads drooping. And they had a right to be tired. The time for the second heat was 7m 49s which meant that Henry’s first heat win was the fastest first four-mile heat ever and Eclipse’s second heat the second fastest. And for Eclipse, this was uncharted territory. Where Henry had run four heats against Washington the previous year, American Eclipse, because he had always been so dominant, had never run three heats in a race in his life.

Henry being washed down.

Van Ranst, who was an excellent trainer, was fully aware that two of the most important requisites in horse racing would be on display that afternoon – speed and endurance. Speed played a major roll in the first two heats, but now, with both horses clearly tired, it would be endurance, coupled with the will to win, that would be the determining factor. It would be the same for the jockeys too. Both Purdy and Taylor were reputed to be among the finest of their day, but they were both getting up in age. Purdy had an advantage in that he was still active while Taylor wasn’t. Though still small and wiry, Taylor had put on weight, and when he weighed in for the third heat he moved the scales to 110 pounds, two pounds over, but a penalty the Henry camp was willing to pay.

The Third Heat

Before the third and final heat began, large groups of fans that had moved out onto the course to stretch their legs were asked to move back in with the crowd outside the rail. Some moved, but much like during the post-parade, most didn’t. Incredulously, no one in a crowd that had bet thousands of dollars complained, at least not openly. John Cox Stevens, aware that the crowd didn’t seem to mind, instead of calling the police in to disperse those who arrogantly remained in the way, ordered the heat to begin anyway, a decision that would be brought up several times in the coming days and one that would always leave a stain on the outcome.

With literally hundreds of people standing out on the track near and around the first turn, which left very little room for the horses to get by, both American Eclipse and Henry were away. The start surprised everyone. Where Henry had spurted to the front right from the start in the first two heats, and no doubt would have again if Walden was still riding him; this time it was American Eclipse who broke on top. Purdy tapped him with the whip several times and they burst to the front and had a two-length lead as they moved into the first turn, then suddenly found themselves in trouble as they were literally surrounded by those arrogant fans that remained on the track, many close enough so that if they wanted to they could have reached out and touched the horses.

Crowd on the track in the first turn.

Luckily, both jockeys were veterans who, during their careers, had seen it all. Purdy’s response was to do his best to ignore them, and he encouraged American Eclipse to plow ahead. Taylor was nervous, too, but he didn’t want to lose more ground because of fan interference, and he pushed Henry on. If someone was stepped on, that would be their problem. Fortunately, no one was and Henry, despite running with caution, didn’t slow and kept close to Eclipse.

Leaving the crowded section of the turn, they continued around it and moved into the backstretch. Purdy kept encouraging American Eclipse, not wanting to let Henry relax, and the champion opened up a five-length lead and yet was still running with an easy cadence. Looking ahead and realizing how easily the champion was running, Taylor was suddenly faced with a dilemma, and this before they were little more than a half mile into the heat.

Afraid that he might lose sight of Eclipse, Taylor encouraged Henry to get closer. Going around the far turn for only the first of four times, both horses were running fast, maybe too fast, and as they passed by the finish line for the first time, Purdy suddenly slowed Eclipse down to a more sensible pace. He had accomplished what he had set out to do: grab the early lead and make Henry run a little. Now, it was time to let a more sensible pace take over.

Once again, as they moved into the first turn both horses encountered trouble, though not from themselves. The fans on the track continued to crowd too close, making horse and rider uneasy. Luckily, there were no incidents, save for the horses’ nervousness, though there easily could have been. The more experienced American Eclipse took it best, but Henry showed remarkable control in keeping his composure.

Moving into the backstretch and away from the crowded part of the track, Purdy encouraged Eclipse to speed up. The horse obliged, and this time so did Henry. On they went as they moved around the far turn for the second time, and turning into the home stretch, they once again moved quickly towards the finish line which, unbelievably, was still crowded with fans standing on the track. At this point, both horses were matching strides, in single file, five lengths apart. And as they moved past the crowd both had become more accustomed to the fans standing on the track and passed by them without incident.

Turning into the backstretch, Eclipse maintained his five-length lead, both horse’s strides measured, almost deliberate, as they continued on at an even pace. Taylor was pleased because Henry was saving some energy for a final desperate try. But so was Purdy. Eclipse continued to feel strong under him, and he knew that the great horse still had something left in reserve.

And then they passed the finish line for the third time and once again plowed their way past those fans on the track, again without incident. There was now but a single lap to go. Eleven laps and eleven miles of afternoon racing were behind them with just this one mile left, but it would be by far the most difficult of the twelve.

Moving into the first turn for the final time, Taylor sensed something, that maybe American Eclipse was ready to falter, and he suddenly went to the whip and asked his horse to go. Like a true trooper, Henry responded, and as they swung out of the turn the southern crowd erupted as he began to cut into the lead. By the mid-point in the backstretch, the lead was down to four lengths, and when they moved into the final turn, it was three. Taylor was pumping, moving in perfect synchronization with his horse, while Purdy was sitting motionless as if he didn’t realize what was happening. The crowd did, though, and they watched intently as two classy, but tired horses rounded that final turn and swung into the stretch, some in hope and others in fear as the lead had dwindled down to two lengths.

With about a quarter of a mile to go, the Union Course was rocking like it never had before. Every northern fan’s eyes were painfully glued to American Eclipse, whose cadence was slowing. Some whined and cried as they clearly saw that their hero, the great hope from the North, was fading, that he was done, and age and a grueling hot sun had caught up and were crushing his spirit. They even believed that the still stoic Purdy had probably given up too, that he himself realized that he couldn’t get even a little more out of his horse.

As the finish line came into view, Henry had drawn almost even with a clearly spent Eclipse. Southern fans were jumping up and down and screaming, believing that their horse was going to win it. Northern fans, those who refused to give up hope, were screaming at Purdy to do something……anything. Many were wondering how he could have made such a magnificent move to win the second heat, a move that fans would talk about for ages, only to sit and, with the entire outcome on the line, let his horse lose and not even try and do anything to prevent it. But this wasn’t Billy Crafts riding American Eclipse. This was Sam Purdy, one of the best jockeys on the planet. He was a master of technique and an even greater strategist. He wanted every ounce of Eclipse’s strength saved for those final desperate yards, for the horse’s strong resolve to kick in and ignite his flaming desire, for his spirit to rise up and preserve what had been such a marvelous career.

Amidst a roar that could be heard for miles, suddenly, Purdy’s arm was raised and then lowered. The whip came crashing down and stung Eclipse on the hind quarter and, in doing so, released a pang of defiance, a tremendous will to win that roared through the mighty horse’s veins and exploded in his heart. After all, it was heart that made the great ones so great and encouraged that special resolve that drove them on.

Eclipse instinctively knew what was expected of him. Even after all those grueling miles, the scorching heat, the screaming fans, and the sharp sting of the whip, at a time when a lesser horse would simply have given up, Eclipse didn’t. He was a marvelous champion, after all, the best horse of his time, and he responded.

The crowd screamed and roared, many so excited that they were literally jumping up and down when the great horse suddenly lunged forward. He picked up speed and once again matched Henry’s strides. He was still in front and was refusing to give in. And then Henry, himself having given so much, suddenly had no more to give. Shocked southern fans, who just mere seconds before smugly visualized victory, were stunned when they realized that his rally wasn’t going to be enough. Their Henry had hit the proverbial wall that all racehorses had to deal with. He was finished and both horse and jockey felt helpless as the so-called thrill of victory was suddenly snatched away by the jaws of defeat.

Never before had a crowd roared with the intensity that exploded from the Union Course that afternoon. People who were miles away would later testify that they could hear it as it rolled across the fields, sounding like a giant wave crashing up on a sandy beach, the roar becoming its loudest when Eclipse rushed past the finish line.

American Eclipse winning the third heat and the race.

Both horses were immediately pulled up, both puffing and grunting as they had given their all. For both, it truly was a marvelous effort, definitely one for the ages. After running 21,120 feet for the third time on a viciously hot and humid afternoon, Eclipse had won, his margin of victory about ten feet.

Immediately after the two horses shot past the finish line, the track in front of the grandstand, where the winning ceremony was about to take place, was a sea of humanity as ten thousand people jammed together. Most of them were jumping for joy and hooping and hollering in victory, while others, those who backed Henry, were stoic in defeat. It took a few minutes to clear a path for the horses to come back to the front of the grandstand to be unsaddled and allow the jockeys to weigh out so the race could be declared official.

The crowd honoring American Eclipse.

When the two horses returned to their handlers, both their heads low, barely above the ground, and every step they took was labored, which was reflected by the time of the third heat: 8m 24s. The afternoon sun showed them no mercy, beating down on their spent bodies and causing their blood to boil. Their coats were sweaty, and foamy suds mounded around their mouths, lathering like white soap suds on their necks and rolling down their inner thighs. Their eyes were glassy, and their ears drooped, a sign of utter and complete exhaustion. In a grueling day of racing, they had run a total of twelve miles, the equivalent of nine and one-half Kentucky Derbys or eight Belmonts. When we consider that the three Triple Crown races total just under four miles in length, then these two gallant thoroughbreds had just run the equivalent of three complete Triple Crowns……..and they did this all in a single afternoon in a time of less than two hours.

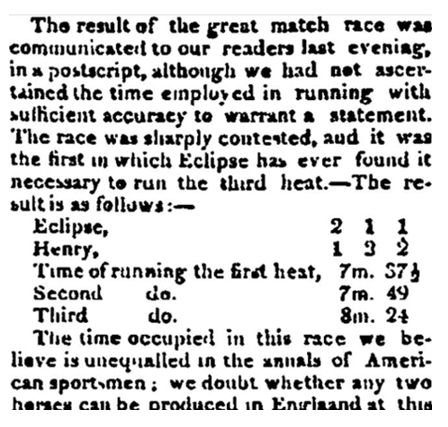

The Gettysburg Republic account of the race.

The next day a bitter William Ransom Johnson reviewed the details of the great race. He was astounded that Henry should win the first heat in record time and yet still lose, even to a great champion such as American Eclipse. In his mind, there could be no doubt that if Crafts had retained the mount on the great horse in the second heat, Henry would have won.

What really discussed him was the crowd that flooded onto the course. He reasoned that Henry was a young horse and very skittish, while American Eclipse was much older and much more mature. He scoffed and grumbled that an incident like this would never happen on a southern track, and he hotly vilified the management of the Union Course for allowing such a deplorable incident to happen.

The next day he drafted a letter and sent it to the Virginia Times. “We Southerus all assembled here in fine spirits and joined in the contest with strong resolution. We have lost the battle but are not vanquished. Could we have had an open course to run upon, and not upon the crowd, as was the case, we should have beat the race as ours is the best horse. The first heat was taken by Henry, and he strongly contested the 2d and 3d.”

Johnson’s letter was reprinted by the New York Evening Post the week following the race, and the paper countered with this reprisal. “We are somewhat surprised, we must confess, to find such a letter running the rounds of the Southern papers. The course, we are free to admit, was not as clear as we would have wished to have seen it, but it is denied in the most direct manner that it was so obstructed at any time as to prevent Henry from winning either heat. It has been admitted by all hands that the whole business was conducted in a manner fair and honorable.”

Johnson no doubt believed that the reason for his young horse’s defeat was the crowded racetrack, even when it was mentioned that the crowd also affected American Eclipse. Still angry, he drafted a letter and issued a challenge for a rematch for a purse between twenty and fifty thousand dollars at the Washington Course later that fall.

Van Ranst politely refused.

It is interesting to note that the Union meeting lasted several days. The next day, Wednesday, Betsey Richards won both heats in a four-mile heat race. The Thursday races were rained out, but on Friday, Flying Childers easily won both heats in a three-mile heat race. On Friday, in the final race of the meet, Henry was entered in a two-mile heat event and easily won both heats.

In summarizing the meeting, American Eclipse had won The Great Match Race and, as such, continued to be called the greatest racehorse in America. This ruffled Southern feathers, but they did gain one measure of revenge. During the entire meet, the North only won a single race, and that was Eclipse’s victory over Henry, a victory that would forever remain tainted in their minds.

The Great Match Race was American Eclipse’s final race. Soon after, Van Ranst sold him at auction for $8,050. He stood for a period of time in New York and sired his best son, Medoc, who would eventually become a top sire.

American Eclipse was later leased to James J. Harrelson, who owned Sir Charles and was eventually sold to William Ransom Johnson, for whom he stood at stud for several years. He sired some notable fillies, including Ariel, a winner of forty-two of fifty-seven races, and Black Maria, whose dam was Lady Lightfoot. He passed on July 11, 1847, at the age of thirty-three, in, of all places, the state that would eventually become the birthplace of many of the sport’s greatest racehorses, Kentucky.

Henry raced for two more years and won several races but was retired at six after he went lame. He was purchased by John Cox Steven’s brother, Robert Livingston Stevens, and stood in the North where he had a modest stud career. Ironically, the two horses that represented areas of the country that were rapidly pulling away from each other eventually changed sides when they finished their racing careers and began their new careers at stud.

Robert Livingston Stevens

The Great Match Race and other important races between the North and the South were a turning point in North America’s thoroughbred horse racing history. Though the South dominated that five-day meet at the Union Course, the next eleven years would see a gradual change. During that span, William Ransom Johnson would manage the South’s interests in a series of thirty such meetings, and the realization that the South was no longer so dominant would set in when the North managed to win thirteen of those contests and continue to have a decided edge when the top stars came together.

Not much is known about Cornelius Van Ranst after he sold American Eclipse. He operated in the shadow of William Ransom Johnson, which from all accounts, favored him as he was one that shunned the limelight. Johnson, on the other hand, was famous, and the press continuously followed his career, both in politics and on the racetrack. Sadly, The Napoleon of the Turf contracted the flu while at a race meet in Mobile in 1849 and died. He was buried alongside Sir Archy, who is also a member of the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame (1955), at his Oakland Plantation in Chesterfield.

Samuel Purdy, who was in his fiftieth year when he rode American Eclipse in The Great Race, retired from the sport shortly after winning the greatest race of his career. Though not formally educated, he became an astute businessman in New York and put his architectural expertise to good use by designing and building homes. He also served on the boards of several banks and insurance companies. He died on December 3, 1836, while living in New York City and was honored by being inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 1970, joining American Eclipse, Sir Archy, and Johnson.

Throughout the balance of the eighteenth century, there would be many match races, but only a very few would be considered on the same level as The Great Race. In a continuation of the North-South rivalry, in 1842, Boston, representing the South, faced the outstanding filly, Fashion, who was the darling of the North, at the Union Course in Long Island. Approximately sixty-thousand people crowded the course, and most of them cheered for Fashion as she upset the great horse and, in doing so, set a four-mile heat record of 7m 32s.

In 1845, Fashion met a southern mare named Peytona, and once again, a race of this magnitude was held at the Union Course and again in front of a huge crowd. This time, the South finally got its revenge as Peytona won in straight heats. This would be the last such North-South battle. The horsemen continued to be friendly with each other, but the differences between two distinctively different parts of the country were continuing to widen, and for both, horse racing would be put on the back burner, and a much larger battle would soon dominate the country.

Peytona defeating Fashion, finally a major victory for the South.