The Great Race of 1823

By: Walter Lazary /// August, 2024 /// 7,783 Words

Part Two

Col. William Ransom Johnson

Col. William Ransom Johnson, a scion of a prominent family in Warrenton, North Carolina, had already carved a niche for himself as a successful businessman and a well-known politician, having served several years as a Virginia state senator. But there was another side to this legendary forty-one-year-old, and it made him one of the most celebrated people in the South.

Born in 1782 in the Halifax region of North Carolina, Johnson was driven by an unyielding passion for horse racing, a legacy he inherited from his father and nurtured from a young age. His career was a tapestry of triumphs that reshaped the careers of the thoroughbreds he trained and the sport in general. His horses were not just successful; they were record-breakers, one of which shattered previous purse records when it won a $30,000 race in 1816. Over the years, his dominance became legendary and perhaps peaked during the 1807 and 1808 seasons when his horses triumphed in an astounding sixty-one of sixty-three races, a winning percentage that remains unmatched by any American trainer of more than fifty races. His extraordinary achievements, coupled with his strategic acumen, earned him the title ‘The Napoleon of the Turf‘ and a revered place in the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 1986, a testament to his unparalleled success and the lasting impact his contributions had on the sport.

William Ransom Johnson

Johnson owned the Oakland plantation in Chesterfield County, Virginia. He also personally owned more than twenty racehorses, which were joined by many others that he trained for various owners. This enabled him to build the largest and most powerful thoroughbred stable in the country, one that flourished with string after string of remarkable horses that, over the years, included many of early racing’s greatest stars, among them Sir Archy, Boston, and the excellent fillies Vanity, Argyle, Maria, and Trifle. But his success as a trainer, and what truly set him apart from others, went beyond his genuine love and respect for horses. It was his strategic brilliance – his unique ability to evaluate the competition and instruct his jockeys on the best race strategy. He knew exactly where to position his horses, when to pull ahead, and at what point to apply the whip. This strategic expertise was often the key element when evaluating the positive factors that led to his numerous victories and his growing legacy as a top racehorse trainer.

One horse that Johnson grew attached to was Sir Archy, whose original name was Robert Burns. Bred by Virginians John Tayloe and Captain Archibald Randolph, Sir Archy was foaled in 1805 by the mare Castianira and was reputed to be Diomed’s greatest son. Johnson liked the two-year-old colt, and he encouraged Ralph Wormeley to purchase him, which he did for a nominal sum. Before the transaction was completed, however, Mr. Tayloe changed the colt’s name to “Sir Archie” (it was later misspelled with the “ie” being replaced by “y” and remained that way).

Sir Archy

Sir Archy made his first start late in his three-year-old season in Washington, D.C., but despite his enormous potential, he was distanced by Bright Phoebus. In his next start at the Fairfield Course in Richmond, Sir Archy was distanced in both of the first two heats, one of which was won by Johnson’s excellent mare, Maria. Sir Archy then rebounded and won the next heat before Maria won the final one. Despite the colt’s uneven performance – having been distanced, as well as winning a heat – Johnson was impressed, and before the day was over, he purchased the still-green youngster for $1,500.

When he was four years old, Sir Archy finally justified Johnson’s belief that he would become a star (Johnson would later say that he was the greatest horse he had ever seen). That year, the vastly improved colt dominated, winning five of his six starts. He also became the best four-mile heat horse in the country, winning four of his five starts at that distance and, in several of those races, distanced his competitors. In a race at the Scotland Neck Course in Halifax, North Carolina, Sir Archy’s single-heat time of 7m 52s in the first heat against a horse named Blank was an American record. In the audience that day was Gen. William Davie, the governor of North Carolina, who was also a noted breeder. He was impressed with Sir Archy’s performance, and when the gallant colt won the second heat by a length in eight minutes flat, Gen. Davie offered to buy him for $5,000, which Johnson accepted. Sir Archy never raced again as he was immediately retired to stud.

********

With the formal challenge put forth by the South having been accepted by Cornelius Van Ranst, Johnson realized that he had a lot of work to do. One key stipulation that he had insisted on and for which he had an iron-clad agreement in writing was that the South’s challenger did not have to be named until just before post-time of the first heat – which was nearly six months away. And the challenger could literally come from anywhere, as long as it wasn’t considered a horse from the North.

Despite these stipulations, the cagey trainer was still up against it. At the time, the South’s best horses were proven winners, Sir Charles, Lady Lightfoot, and Sir Walter, but they had all faced American Eclipse in the past without success. Lady Lightfoot, who was now ten, might have been up to the challenge when she was much younger, but now she was too old and past her prime.

As for Sir Walter? Bela Badger’s home-bred son of Hickory had been soundly defeated by American Eclipse, not once, but twice, and Johnson felt that his performances tended to be mediocre far too often. Not surprisingly, both Lady Lightfoot and Sir Walter were quickly ruled out, as was Sir Charles, who was probably still the best horse in the South but was now retired because of his injury.

With six months to go before the big race, Johnson admitted to several other prominent horsemen that their task wasn’t going to be easy. However, the key was the six-month time frame, and Johnson, who had a reputation for being patient, decided to take his time and spend the winter months evaluating dozens of horses. When many of the South’s most successful horse owners were made aware of his plan, they immediately responded and brought their best horses to him. All were subjected to a series of lengthy works, mainly geared towards speed and endurance, and Johnson continued this vigorous program every day for many weeks.

Johnson evaluating the best race horses in the South.

Finally, after a trying period during which every horse was given a fair chance, Johnson narrowed his list of possibilities down to five. Many thought that eight-year-old Sir William and six-year-old Muckle John, two of the South’s finest and most successful horses in recent months, would be at the top of the list. Sir William, a son of Sir Archy, was proven at several different distances, including four miles, and had won more than twenty races in his career, including two victories over Sir Charles in their four meetings. Muckle John was also a classy horse, and his impressive resume included a victory over Sir William.

When Johnson announced his candidates, there was both surprise and dismay. The South’s two top horses were not considered, mainly because of their age. Sir William and Muckle John would both have to carry the same weight as American Eclipse, which was 126 pounds. A key component in Jonson’s plan was to take advantage of the Union Course’s scale of weights, which heavily favored younger horses and fillies, and he kept this in mind as he worked through his list of candidates.

What was also important to the wily trainer when making his choice was that his challengers be from the Sir Archy line, the mighty stallion that was now the country’s most successful and influential sire. Four of the top five were sired by the great stallion, and the fifth was sired by his son.

As the training process continued through the winter months, many believed that Johnson’s leading candidate was four-year-old John Richards, a solidly built horse with a bullish manner and proven stamina to run in four-mile heats. His full sister, the five-year-old mare Betsy Richards, was also gifted with her brother’s stamina and lengthy stride. Both displayed an heir of superiority and had handled themselves well during the preliminary weeding-out process and, as such, were easy choices to stay on.

The third horse chosen was a six-year-old named Flying Childers (with the same name as England’s Flying Childers). Though he was rated slightly below the Richards horses, he was a tough, no-nonsense type runner, the winner of several four-mile heat races, but he had also lost several races to Sir William and Muckle John without ever having beaten them. When questioned as to why Flying Childers was added to the list when clearly there were other candidates that appeared to be better, Johnson replied that it was because of his work ethic. Flying Childers had a reputation as being a hard-working horse that could withstand vigorous training, and when he ran in a race, it took a horse with extraordinary talents to beat him. It was hoped that his competitive desire and strong work acumen would rub off on the others.

And so as much as people scoffed at the idea that Flying Childers should be included in Johnson’s list of five, while horses like Sir William and Muckle John weren’t, they were totally flabbergasted when the names of the final two were announced. They were young and relatively unproven three-year-old colts named Washington, who was sired by Sir Archy’s son, Timoleon, and Henry, the fourth son of Sir Archy. Both had obvious talent, but what really interested Johnson was the fact that if they ran against American Eclipse, even though, according to the Union Course Scale of Weights, they would both turn four on May 1st, they would still have a considerable weight advantage and only be required to carry 108 pounds compared to the champion’s 126. This fact was a must as far as Johnson was concerned because, in his mind, perhaps the greatest key to defeating American Eclipse was having a large weight advantage.

Though both horses were only three, Washington was months older and was much more mature and advanced. Henry was a June foal and still theoretically a two-year-old, but Johnson felt that he had potential. In fact, he often confided that he could sense it. “It’s well hidden,” he would say. “Smothered in a mishmash of bad traits. But it must be corrected if he has any chance of defeating American Eclipse.”

Henry

Henry, who some called Sir Henry, was bred by Lemuel Long of North Carolina, and though he could not be considered striking, he was certainly on the verge of becoming an imposing figure. He was a chestnut with broad shoulders and well-muscled flanks, and yet he was lean with prominent ribs, typical of young horses that are still filling out. Johnson’s biggest concern wasn’t his physical appearance but rather his attitude. Henry possessed a young horse’s tendency to revolt and was often headstrong. He was also very spooky, not a good thing on a noisy racetrack with fans, many of whom were almost standing on the racing surface, yelling and often screaming. What interested Johnson, though, were his long, powerful strides and the tremendous burst of speed that he could carry for much longer than normal distances.

Henry

Henry had only raced once in his career, a two-mile heat race the previous October when he was a two-year-old. It was a five-horse field and oddly enough, one of his opponents was Washington, a horse that was owned by Johnson’s father. Johnson, who wasn’t present that day, was told that Henry displayed a tremendous burst of speed in the first heat and opened up a sizeable lead, then hung on for a narrow victory over a charging Washington. Buoyed by his first heat win, his owner ordered the jockey to try the same tactics in the second heat, and he almost succeeded, but this time Washington, who could close like the wind, caught him in the final jump, at which point the judges declared the race a dead-heat.

Washington was a narrow winner of the third heat, and then, in a rarity in heat racing, they ran in a fourth heat. Washington won it, this time going to the front immediately and leading all the way, though he just managed to hang on to win by a half-length when Henry took a run at him.

Johnson was happy with the outcome, which is why he wanted to keep Henry around. He planned to work him hard and hopefully train him away from his bad habits and see if he could improve enough to be taken more seriously. Of the five remaining horses, only Flying Childers was considered behind him at that point, and that was only because of his age.

Despite believing that Henry had tons of potential, Johnson was more impressed with Washington and thought that the tenacious colt had a big chance of being selected to face American Eclipse. That race against Henry was his third lifetime victory, and in winning it, he proved that he had the necessary endurance to win a four-mile heat race. Johnson was also impressed with the colt’s relaxed demeanor. He was always calm and laid back, while Henry was a nervous type, headstrong, and often with a mind of his own. Johnson had long since learned that nervousness meant wasted energy, and one of the keys to winning four-mile heat races was endurance, which required a horse to conserve as much energy as possible.

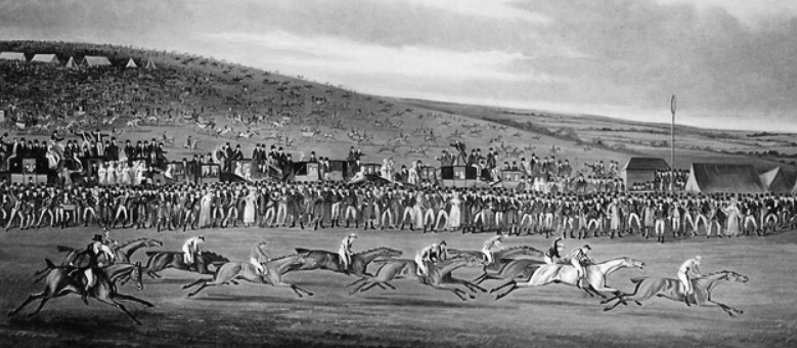

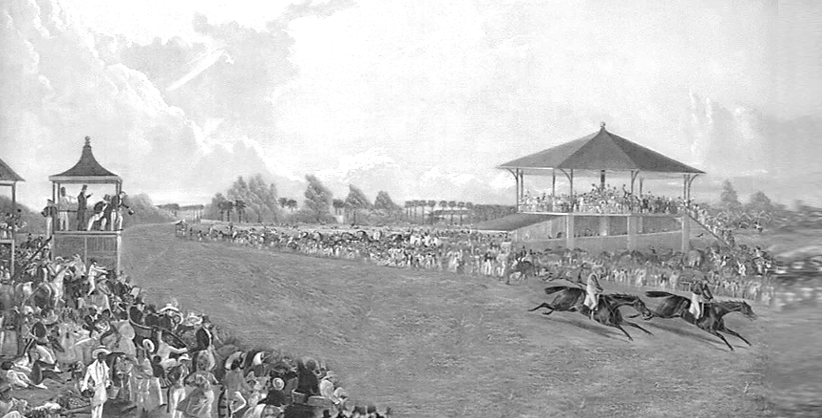

Charleston Race Week

It was suddenly February, and the first race meet of the year loomed large on the racing calendar. Charleston’s Race Week was so popular with horsemen and fans alike that the then-sixth largest city in America was virtually shut down. Businesses and schools were closed, and thousands of slaves were given the day off. The entire city celebrated the beginning of the racing season with parties everywhere, the atmosphere much like Mardi Gras in New Orleans, with most of the talk about horse racing.

At that time, the quality of the sport in Charleston was as good as anywhere in the country, and Johnson was anxious to see how his horses competed against other top horses, especially after he had worked with them for so long. He decided to take the oldest two, Flying Childers and Betsy Richards, and enter them in races. He left the youngest three back on the farm with assistant trainer Robert Taylor, an ex-jockey, to continue their development.

Charleston Race Week

On opening day, there was a four-mile heat race with just two starters. The turf was very soggy after several days of rain and the race lasted just two heats, both won by a horse named Sumpter. The five-year-old was spectacular and won each heat in about eight minutes, the time deemed excellent considering the terrible condition of the course.

During the next two days, both Flying Childers and Betsy Richards ran in their respective races. Childers’ race was a three-mile event, which Johnson chose to help build up his speed. The determined colt didn’t disappoint and dominated, winning it in consecutive heats. Betsy Richards’ race was an even shorter two-mile event. She put a smile on Johnson’s face as she won both of her heats by wide margins.

The final event of the four-day meet was a three-mile heat race called the Silver Plate Handicap. Being a handicap and not a weight for age race, the judges were free to assign weights to the participants based on their records. Just three horses were entered, Flying Childers, who was assigned 112 pounds, Betsy Richards at 99 pounds, and a gelding that had finished third in a race a few days before at 107 pounds.

The first heat was off under bright sunshine. Betsy Richards immediately sprinted to the top, her long strides dwarfing Flying Childers’ much shorter ones as she chugged along on the lead. It was not until the final turn in the final lap that Flying Childers made his move, his short legs churning like a speeding windmill as he glided over the soft turf. He made a strong, unrelenting run at Betsy and, with a tenacious effort, forged into the lead in the deep stretch to win the heat by two lengths.

It was said that Johnson was surprised by the outcome as he fully expected Betsy Richards to win. She ran very well early on, but he was disappointed with her closing effort and thought that a change of tactics might be beneficial. During the customary half-hour break between heats, he ordered the jockeys to reverse their horse’s running styles.

When they were off in the second heat, this time Flying Childers bounded into the lead at the start. He maintained it without being challenged until the final turn on the final lap when it was Betsy Richards’ turn to take a run at him. The filly gained rapidly, but in the deep stretch, when it appeared that she would go past, Childers dug in and pulled away for an open-length victory.

Flying Childers pulling away from Betsy Richards.

Though Flying Childers had shown up the mare, Johnson felt that she might have needed a race to be at her best, and despite her loss, when he left Charleston, he was smiling. All in all, he was pleased with the efforts of both his horses. All that hard work and training was paying off. He was even more pleased because having arrived in Charleston with two horses, he would leave with three. He had been particularly impressed with Sumpter and purchased the horse for $2,400. Suddenly the list of five challengers grew to six.

********

The winter months rolled into March and with the Great Race just over two months away, Johnson decided to up the training regimen. He trained his small selective group vigorously, running them in brisk training races often six, eight, and ten miles in length, and he never gave them time off. They trained for six days, and then on Sundays, they would run in the training races against each other and sometimes against other horses that appeared to be nothing more than sacrificial lambs.

And as the great trainer had hoped, with the passage of time, the younger horses began to show marked improvement and were now taken even more seriously. The three youngsters all had different characteristics. John Richards was a bullish type, and there was always a confident glint in his eyes. He had a penchant for running on the lead, much like that of a great stallion when leading his herd, and when he dug in and was going full out, his long powerful strides measured close to twenty-five feet. He had also been gifted with limitless endurance, often not even breathing hard after a particularly tough effort.

In contrast, Washington was a very reserved and mature young horse, yet he was gifted with a fiery competitive spirit – obviously a horse that didn’t like to lose. He was also versatile, capable of setting a good pace while on the lead, though he was best at coming from off the pace with a quick burst that often carried him to the front.

Of the three, the skittish and immature Henry was still considered behind. He was the fastest of the group over a distance and probably would be best on the pace, but he needed to learn how to relax and follow his jockey’s orders.

In late March, Johnson decided to pit his six finalists together in a serious trial race over his Oakland course. This was a straight course, and the horses would run two miles down a long stretch, make a rather sharp turn, and then run two miles back. Henry’s jockey was a small, wiry, twenty-six-year-old white man named John Walden, a farmer’s son from Virginia. The riders on the other five horses were all slaves, which was normal during that period.

When the race began, Henry, despite Walden taking a strong grip and trying to hold him back, quickly sprinted into the lead. He charged down the long straight like a rocket, but all those who were watching realized that if he kept up his pace without being rated, he would never last the four miles.

Walden was a particularly good rider, strong and an excellent judge of pace, but he had his hands full. He constantly had to fight Henry while trying to hold him back, but the young headstrong colt would have none of that and continuously shrugged him off. In the meantime, John Richards, who hated running behind horses, allowed himself to be patiently rated while Henry chugged away in front of him, and he remained two lengths back. It was another three to the team of Flying Childers, Betsy Richards, and Washington, while Sumpter, not looking good, was well back.

Rounding the turn, they then headed back. Henry maintained his lead through the third mile while continuing to rebuff Walden’s efforts to restrain him. Johnson watched forlornly and shook his head. He knew what was coming almost before it happened, and he watched dejectedly when the stubborn three-year-old’s stride, so powerful and effortless early on, was now becoming shorter as he was clearly beginning to labor.

Johnson knew that this was the time when John Richards should pounce, and the suddenly eager colt did. As if on cue, the bullish four-year-old’s stride suddenly lengthened, and he roared past his younger rival and on to win the race rather easily by five lengths. It was a decisive victory, but more importantly, he showed Johnson that despite being a horse that wanted and often needed the lead, he could be patiently rated without sulking and still have plenty left for the final closing run.

Henry, who was now totally spent and was rapidly retreating towards the back of the pack, was helpless when Washington zipped by him. His closing effort was enough to secure second place while showing Johnson that he was improving in the right direction. Following were Betsy Richards and Flying Childers, while Henry faded to fifth; the only thing saving him from being last was that Sumpter had gone wrong and was pulled up.

John Richards’ victory wasn’t surprising, but Johnson hadn’t expected it to be so resounding. The young four-year-old had been his favorite going into the practice race, and now he was without question the clear-cut favorite to represent the South, while Washington was now his second choice.

Henry’s stubbornness was clearly causing his development to fall well behind the top two and the concern was that there was precious little time to make it up. Even so, Johnson was not yet ready to give up on him. He could see a world of promise sitting just below the surface and he continued to work with the colt to correct those areas of concern, mainly his stubbornness and his apparent disdain at being rated.

Racehorses are creatures of habit and have a stubborn resolve not to change these habits. It is this stubbornness that all too often affects their performance on the track – speed horses that refuse to rate and burn themselves out – horses that refuse to put out when running inside other horses and thus lose valuable ground and momentum – and horses that gain the lead and then slow as they wait for the field to catch up. Henry was about as stubborn as a horse could be and it was his refusal to give in and allow his trainer to change his ways that was slowly leading to his demise.

Johnson was perplexed but refused to give up, which was one of the many reasons why he was considered the best trainer in the country. In the end, it was his own stubborn resolve that would begin to pay off. In the ensuing days after the practice race, almost as if by magic, that promise that he waited to pop to the surface suddenly showed. Henry, possibly realizing that his continued stubbornness was to no avail, began to give in and, little by little, allowed Walden to rate him. It was a small step in the right direction, but it was a necessary one.

********

March rolled into April, and the day of the great race was creeping closer. The horses had worked long and hard, and their daily routines were becoming boring. They needed actual race action, and Johnson finally decided to run them in meet races, which were necessary for him to complete his evaluations.

There was a course in Petersburg, Virginia, called Nottoway that was conducting a short meet. It was built in the middle of a forest, and much like a ‘B’ track today, it attracted small crowds, mainly locals and lower-class horses. The crowd that attended the Nottoway races was never large, but on this day, the small stand that could accommodate maybe sixty people was full, and there was a line of excited farmers and town folk standing along part of the front stretch.

John Richards was the main attraction and would run in a three-mile sweepstakes. His jockey was a fifteen-year-old slave named Charles Stewart who, despite being so young, when it came to race riding, was old beyond his years. When only two other horses were entered, locals named Tyro and John Stanley, neither of which Johnson thought would be much of a test, the wily trainer decided to make John Richards work hard to get the win and entered Flying Childers.

In the first heat, the robust four-year-old charged into the lead and soon extended it to three lengths over Flying Childers as the two locals quickly dropped well back. As the race progressed through the second and on into the third and final lap, John Richards was still in front and running effortlessly. Johnson, thinking that the horse was winning too easily, wanted a sterner test, and as the field passed by for the final lap, he waved at Flying Childers’s jockey to step it up. The jockey nodded, and Flying Childers, looking like he had been stung by a bee, suddenly bolted after his younger stablemate.

As the town folk and farmers watched John Richards gallop around the course in a relaxed and confident cantor, suddenly, the complexion of the race changed. Flying Childers, who was now running full out, was beginning to make up ground, and the lead of about seven lengths was narrowing rapidly. Johnson watched as they moved into the backstretch and was impressed as Flying Childers made up three lengths in less than fifty yards.

Nearing the far turn, John Richards’ once insurmountable lead had shrunk down to two lengths, all this as Stewart continued to sit motionless. If anything, the little jockey looked like he thought that he had the race won and seemed unaware that Flying Childers was rapidly gaining ground behind him. Watching forlornly, Johnson’s concern showed. He wondered if John Richards would respond, and he began to fear that, much like Henry’s performance in the practice race, he had gone out much too fast and had nothing left.

With Johnson’s fear mounting as the horses moved into the turn, the angry trainer yelled out for Stewart to get into his horse, but to no avail. “How can he not see what is going on behind him?” an angry Johnson mumbled to himself. But then, in an instant, the frown on his face melted away. As Childers was continuing to bear down and look like he was going to go into the lead, Stewart suddenly came to life. With careful and yet powerful strokes, he gave John Richards several smacks with his whip – and it worked. The slap of leather on sweaty horse flesh was harsh, the sharp snaps echoing against the crowded stand. And with each crack, Johnson’s mounting anxiety crumbled as he watched John Richards respond. It was a sight to behold, and as Johnson watched his gallant warrior come to life, his grin stretched from ear to ear as his bullish four-year-old took off and galloped past the finish line five lengths in front.

John Richards defeating Flying Childers at Nottaway.

Johnson was elated. The horse that he thought was the best, in actual fact, really was the best. He had gone out and set the pace and then, with Flying Childers’s stiff challenge on the final lap, opened up and dominated through the finish line. It was a perfect performance that demonstrated once again just how good John was, how he could lead and yet allow himself to be rated so that he had a lot left in the stretch when it counted most, especially against a horse like American Eclipse.

Feeling confident as they lined up for the second heat, Johnson would again have his confidence waver. The horses left quickly, and this time, the local horses got into the action, with Tyro taking the lead and maintaining it into the backstretch on the second lap. Stewart, who was sitting patiently with a horse that obviously wanted the lead and yet was showing just as much patience as his jockey, suddenly cut loose. When he did, John Richards exploded and roared past Tyro, leaving him and the other Nottoway horse in his wake. But John wasn’t the only horse going hard and making a big move. Flying Childers was rolling too, and he quickly caught up to his stablemate near the end of the backstretch.

Wanting a stern test, Johnson was about to get one. With a lap and a quarter to go, his two horses ran into the far turn and pulled away from the locals. When they turned into the stretch for the final lap, they were literally head and head, and they went at each other like this as they ran past the finish line and into the turn. All through the final lap, they were relentless, first one taking a neck lead and then the other, John Richards digging in with his long strides and the smaller Flying Childers seemingly taking two strides to his one but still managing to keep up.

The small crowd was on its feet, cheering loudly as the two gallant horses turned into the stretch for the final time. John had a short lead but then Childers managed to get his head in front with about a hundred yards to go. On they came, neither willing to give up, and just when it looked like Childers was going to nose out his game opponent, John lunged, and they hit the finish line together.

Johnson’s heart was pounding, and the locals were arguing amongst themselves as to which horse had won, it was that close. It took a meeting of the three judges to decide a winner. One judge thought that Flying Childers had gutted it out to get the win by a nose. Another said he thought that it was John Richards, believing that he extended his neck at the line. The third judge sided with the second one, and in the end, John Richards was declared the winner, the decision hotly disputed by many in the stands who had bet on Flying Childers.

Despite the all-out performances of his two horses in the second heat after John Richards had decisively won the first, Johnson left the course disappointed. He admired Flying Childers. The horse always gave his best and earned whatever he gained on the track. He had given the great trainer’s best horse a mighty struggle, but this threw Johnson for a loop because he knew that Childers, even at his absolute best, would never come close to beating American Eclipse.

Newmarket Spring Meet

In early May, the Newmarket spring meet opened. It was the country’s top race meeting where annually, many of the best horses in training would run in races for purses up to a thousand dollars. Newmarket, in Southern Virginia, was aptly named after the famous Newmarket course in England. It was a picturesque place with a lush turf course and a grandstand and clubhouse that were second to none. It was Johnson’s home track, and he was a member of the track’s Jockey Club. If there was ever a time when he wanted his horses to show their best, it was here, in front of his hometown fans.

The highlight of the meet was the four-mile heat race, an event that racing fans eagerly looked forward to. It had attracted many of the South’s best horses over the years, and in the past, it had been won by Lady Lightfoot, Sir William, and Sir Charles. Surprising many, Johnson, who had five horses to choose from, decided to enter Henry, his inexperienced neophyte who had only a single race on his resume and was still considered a maiden. Equally as surprising was the fact that no horses were entered against him.

Never one to be deterred, Johnson decided to enter Betsy Richards, figuring that it would be a good test for both. Shortly after, another horse was entered, a mare named Spring Tail, who was a definite longshot but would help round out the field. It was clear to all, though, that the two Johnson-trained horses were the best, and the question that was puzzling the crowd was which of the two would take that giant step forward and perhaps challenge John Richards – the experienced mare who was tough as nails or the young nervous and headstrong upstart?

The large crowd looked on intently, buzzing and yelling out bets to one another even as the horses moved into line. Then, in the blink of an eye, they were off, and immediately Betsy Richards, and not Henry, sprinted into the lead. Looking on, Johnson’s eyes brightened, and he smiled. He was elated because if there was one thing he wanted, it was for the youngster to stalk the pace early and not go to the front.

Betsy, though a mare, was a very powerful one, stronger than many of the colts that she went up against. She was fast, with a determined manner, and pulling hard against the reins she not only took the lead, but she also opened up. Johnson liked the way she immediately took over the race and the resolve that radiated from her muscular body. But his eyes were on Henry, and he was encouraged by what he was seeing. The young colt, with Walden strictly following orders, was purposely held back under a strong hold, and for the first time, he did not fight the bit, instead trusting his jockey and allowing him to take control. Perhaps the constant schooling was paying off.

The two gallant runners remained one-two through the first three laps, Betsy Richards looking comfortable and Henry showing a newly found patience that he had never shown before. With a mile to go and with the young colt remaining patient, even though it was clear that he wanted to run, Walden decided it was time to see what he was made of. Per Johnson’s instructions, Henry was finally let loose, and like an elastic band that had been stretched and suddenly released, he flung himself forward and took off like a shot. At this point, the lead was seven lengths, but it might as well have been one. Henry, with that blinding speed that Johnson knew was always within, quickly ate up those seven lengths and, with the crowd cheering, rolled past the mare and into the lead.

For Johnson, the wave of emotions that followed paralyzed his mind. Like almost everyone else watching, he thought that the race was over, that Betsy Richards was all through, and Henry would go on to an easy victory, perhaps by many lengths. He was wrong. With courageous resolve, the mare fought back and, with her own determined spurt drawing her almost even with the colt, Johnson was suddenly shrouded by a wave of disappointment as he believed that Betsy would rush by and leave Henry in her wake.

Then it happened, that point in his young career when Henry showed something that he had never shown before but which Johnson knew was hidden somewhere deep within, like a prisoned convict waiting to be set free. It was a tremendous will to win, a characteristic that all the best horses had and a desire that Johnson now knew that Henry had.

In the trainer’s experience, he knew that many horses, after making the kind of move that Henry had made when coming from well back to get the lead, if challenged again, would have nothing left and give up. But this was a different Henry, a newer and much-improved edition, and when he responded to the mare’s challenge, Johnson knew that this colt had the ability to challenge a horse like American Eclipse. He watched intently as Henry tenaciously dug in, and with a stubborn Betsy Richards driving with him towards the finish line, he not only held her at bay, but he also pulled away in the final yards to win by a length. And he didn’t just win. The time of 7m 54s was the fastest four-mile heat ever at Newmarket.

The crowd was buzzing after watching both Henry’s and Betsy Richards’ dramatic performances. But they all knew Betsy, and they were well aware of what she was capable of. Most believed that she deserved to be taken into serious consideration for The Great Race, and finishing within a length of a track record time proved it. But Henry? When the two had lined up for the start of the heat, many in the crowd had never heard of him, and in their opinions, for Johnson to even consider a horse that had run only a single race and was still a maiden to possibly be a legitimate challenger to American Eclipse, well that was absurd. Secretly, many mocked the man they often called Napoleon, especially when Henry was being considered while Sir William was not. But now, after that first heat, the wily trainer had gained even more respect. There were doubters no more.

As the horses lined up for the second heat, Henry seemed eager. He had just run a tiring record-setting heat, and now here he was a half hour later, seemingly full of run. And when the horn sounded, and they were off, it was Henry who spurted into the lead. He wasn’t headstrong or hell-bent for leather either. He was rated properly and yet still managed to open up a five-length lead which he maintained without incident through the first three laps.

Everyone in the crowd was waiting for Betsy to mount a charge, and in that final lap, she did. She made a determined move and gained steadily while Henry’s cadence remained the same as he kept his composure and his focus. When they turned into the stretch, and with the mare now at Henry’s flank, Walden remained calm and began to encourage his horse but not really getting into him. When Betsy’s nose drew alongside Henry’s neck, everyone, including Johnson, fully expected her to go by. After all, that record pace in the first heat would drain the energy from any horse, including American Eclipse.

The cheering was loud and intense like it always was when two horses were driving side by side to the wire. Betsy Richards was tough as nails and looked like she was getting stronger. But Henry wasn’t exactly backing up. He drove on, and then, with the wire one hundred yards away, Walden suddenly went to the whip. Henry obediently responded and, using the last of his reserves, surged and lunged forward and opened up by a length at the finish. The time was 7m 58s, the second fastest four-mile heat time ever at Newmarket. Henry had just set a record for two heats in a four-mile heat race, and he won both those heats in less than an hour.

Henry defeats Betsy Richards at Newmarket.

Later in the meet, it was Washington’s turn. As he entered the track to run in his race, Johnson had mixed emotions. It was no secret that the horse, which was owned by his father, had been a clear second choice, at least after that practice trial when he finished second to John Richards while Henry had faded badly. Since then, however, Washington’s disposition had changed, and with that, his placing. He was no longer number two on the list. He wasn’t working like a top horse should work. He wasn’t putting out and, at times, was hard-pressed to keep up with the others in the trials. And now, after Henry’s extraordinary performance, Johnson considered Washington behind him.

The colt was entered in a two-mile heat race against a large field, which included Sir William. The idea was to get his attention early and hopefully make him focus on the race without becoming disinterested. Looking mature and running with awesome power, Washington won the first heat with ease but surprisingly proved to be no match for Sir William in the remaining two heats. His loss shocked Johnson. Clearly, he was a horse with so much promise, but his development for some unexplainable reason was slowing, a concern the past couple of weeks and now confirmed with his crushing defeat.

Johnson returned to his farm after the Newmarket meet, filled with mixed emotions. Buoyed by Henry’s rapid improvement, his elation was taxed by Washington’s change in demeanor. And as the days began to fly by, another blow! John Richards, the horse that America’s greatest trainer still favored to go up against American Eclipse, suffered a quarter-crack when he was pulled up in a training race just nine days before the big race. Johnson was devastated as he firmly believed the horse still had a big shot with Eclipse. And if that wasn’t enough there was another setback. Washington’s failure to compete was more than an anomaly. The horse continued to regress to the point that he lost his competitive edge and refused to put out, sometimes even refusing to take a step.

Just days before the big race, the always confident and often arrogant Johnson suddenly felt like the world was caving in all around him. Because of injuries, a lack of competitive desire, and Henry’s dominance of Betsy Richards, the group of six possible starters was now suddenly down to three, and one of them, Flying Childers, had already been taken out of consideration.

For the next few days, Johnson was visibly upset. He began to question his training methods. Had he worked the horses too hard? After all, they were horses, not machines. Sumpter and John Richards had gone down with injuries, but could they have been avoided? Probably not. Injuries happen daily in the sport of horse racing. Over time, the constant pounding of thin legs carrying a thousand or more pounds over turf that was often hard and unforgiving can take its toll. But the way in which the magnificent Washington had suddenly quit, his demeanor screaming that he wasn’t injured, that he just had had enough, wore heavy in Johnson’s mind.

With six days to go, it was decided to have one more practice race. The three combatants would be Henry, Betsy Richards, and Flying Childers. They would race at Fairview Farm near the resort town of Bristol just north of Philadelphia. Johnson had stabled his horses there after shipping north on their journey to New York. Still downhearted when the horses lined up, his spirits would be lifted by the time the race was over. Henry was everything that he would want a horse to be when it went up against American Eclipse. He glided over the turf, running easily and he wasn’t even breathing hard when he charged past the finish line a good ten yards in front.

********

All during the winter and spring of 1823, the Johnson horses were constantly in the public eye. In the months leading up to the great race their training and racing progress was reported regularly in the news and discussed at length by virtually everyone in the south that followed horseracing. Conversely, American Eclipse was stowed away on Van Ranst’s farm, quietly and uneventfully enduring winter’s harsh cold and snow while in relative obscurity far away from the public. His coat had become thick and shaggy, and his mane long and tangled. For the most part he looked unkempt, looking more like a milk wagon horse than a thoroughbred, and certainly not remarkable enough to draw one’s attention. There were no trial races or hard daily drills. He often slept in in the mornings while the handful of other horses in the stable worked. His most strenuous exercise was jogging two or three times each week and light training on those days when he didn’t jog.

Nevertheless, as winter drifted away and spring came into bloom, so did the great horse. He was now on a regular training schedule and looked terrific with his coat sleek and his mane combed and trimmed, and most importantly, that competitive fire was glowing in his eyes. The most difficult race in his career was nearing. No one could be sure if, at the age of nine, he would be as good as he was. The man they called the Old Wizard wasn’t sure either. He could only hope.

Van Ranst would make one change before the race, and it would be a major one. He decided to replace his horse’s regular jockey, the veteran Sam Purdy, who was fifty years old, with a much younger though inexperienced jockey named William Crafts. It was a decision that many of Eclipse’s fans were not happy with. They reasoned that Crafts was not only inexperienced, but he was also bull-headed and often shunned instructions and did things his way. Conversely, the ever-reliable Purdy was a clever strategist who knew American Eclipse and wasn’t the type that would rattle and become undone in adverse situations like brash rookies were often prone to do.

There is a saying that held water back then just as it does today: “You should never try to fix something that isn’t broken.” Cornelius Van Ranst would soon learn this the hard way.