The Great Race

On May 23, 1823, a momentous event unfolded at the Union Course in the borough of Jamaica, Long Island, New York. A staggering sixty thousand passionate racing fans from all parts of the country converged to witness a historic showdown – a battle between the legendary nine-year-old American Eclipse, a stalwart of American racing who represented the North, and four-year-old Henry, sometimes called Sir Henry, a promising contender from the South. The air was thick with anticipation as the two horses prepared for a grueling best-of-three, four-mile heat race to decide American horseracing supremacy.

Following is the first of a three-part account of this race and the preparations leading up to it.

On May 23, 1823, a momentous event unfolded at the Union Course in the borough of Jamaica, Long Island, New York. A staggering sixty thousand passionate racing fans from all parts of the country converged to witness a historic showdown - a battle between the legendary nine-year-old American Eclipse, a stalwart of American racing who represented the North, and four-year-old Henry, sometimes called Sir Henry, a promising contender from the South. The air was thick with anticipation as the two horses prepared for a grueling best-of-three, four-mile heat race to decide American horseracing supremacy. Following is the first of a three-part account of this race and the preparations leading up to it.

PART ONE

Manhattan, New York City, May 20, 1823

It was an exciting day in the lower part of Manhattan, one of those moments in time when you feel that you’re in the presence of greatness. People milled about, hundreds of them – men, women, teenagers, and young children. They lined both sides of the street as they waited, some patiently, while others were growing impatient, for their hero was coming, though on this day it wasn’t a man, a woman, a politician, or a soldier that they were waiting for. It was a horse.

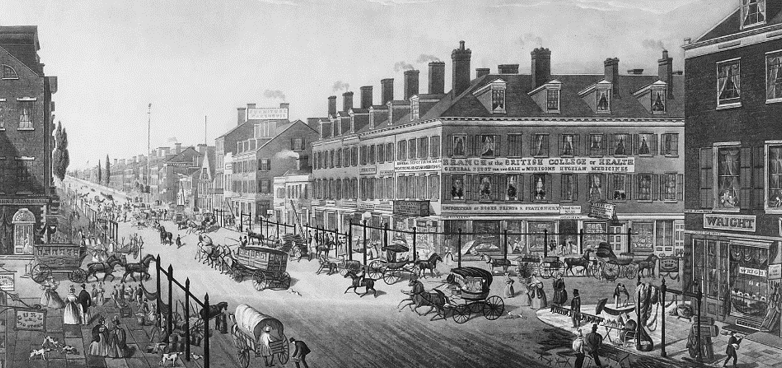

In this age of paved roads and high-speed automobiles, one of the last things one would expect to see walking along the busy car-clogged streets in a large city would be a horse. But this is the twenty-first century, and the world is far different now than it was back in 1823 when it wasn’t unusual to have an equine presence crowding the busy streets of Manhattan. After all, this was the horse and buggy age, a time when the streets were a colorful gathering of horse-drawn carriages, and people mounted on horse-back or driving wagons and buggies as they made their way along the dirt roads that crisscrossed and meshed together in this rapidly growing city.

Manhattan, New York City – Early 1800s

For the people of that era, a horse was often more than just a mode of transportation. It was a symbol of power, grace, and resilience – and the horse that they were waiting for and had inspired such a large, enthusiastic crowd to stand under a brutally hot sun had proven time and time again that he was no exception. He was a living legend, his regal reputation having captured their imaginations, so much so that in a time fraught with uncertainty, he gave them strength and was their beacon of hope.

As the people waited, the atmosphere was electric, and a loud buzz accelerated and swirled through the crowd as the great horse drew near. Then someone shouted: “Northern Eclipse is here!” – this magical moment instantly becoming a snapshot in the memories of so many, most of whom had never been this close to him before.

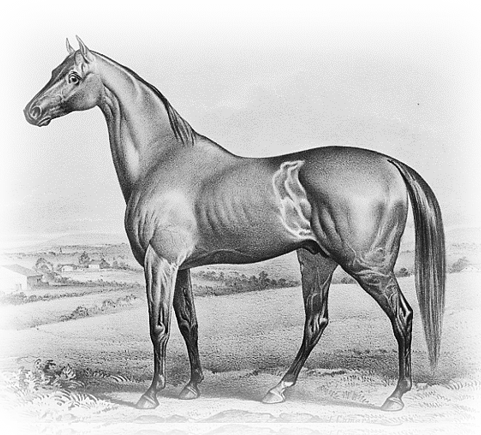

The crowd pushed closer to the edge of the road as the great horse came into view, guided by a handler on each side as he snorted his way forward. He was not what one would call a remarkable specimen. He stood just over fifteen hands high and was smaller and blockier than most other stallions. But there was something about him – a certain spark in his eyes, the grace and self-assuredness of his movements – that set him apart. He was the recipient of excellent care, and it showed. He was a deep copper-colored chestnut with a small white star on his forehead and a smidgen of white on his lower hind leg. His coat, both shiny and smooth, was drawn tight over a thick mass of bone, and with every step, waves of sculpted muscle rippled across his flanks, hinting at an awesome power within.

American Eclipse

For those who had gathered, there was no mistaking the compact and yet powerful physique of a thoroughbred racehorse, which he was, of course, and as his handlers continued on and led him past hundreds of his adoring fans, he was eagerly embraced, for the people loved him. He represented so much for them, a northern ray of hope in a country whose political and humane differences were escalating and threatening to push them even further apart.

To the people in the North, Northern Eclipse was an icon, the best racehorse of his time, and many were saying of all time. So good was he that he had yet to experience defeat. In fact, in his seven career starts, which consisted of exactly thirteen heats, he had never been tested in any of them.

The heat that morning was building as American Eclipse proudly pranced past his devoted fans, his thick neck bowed and gait effortless, his intelligent eyes keenly focused, and his ears pricked straight up and ever alert. He was making his way from his training center at Harlem Lane out to John Cox Stevens’ estate on Long Island to complete preparations for what would undoubtedly be the biggest and most important race of his career, a demanding test against an unnamed challenger from the South that would forever be called The Great Race.

American Eclipse’s owner, Cornelius Van Ranst, was not in favor of parading his prized star along the crowded streets of Manhattan so that people could see him. This was an idea put forth by Stevens, who, along with several others, owned the Union Course. A successful businessman, who always had a flare for dramatics, Stevens had contacted the city’s newspapers and informed them that the great horse would be parading along certain roads on his way out to Long Island, and he asked them to encourage the public to come out and catch a glimpse of their marvelous hero. It was a ploy that he hoped would generate even more interest in the big race though no one had any idea that it would create this much.

The excitement that gripped the people as the great horse walked by was incredible. Some became so enamored that they fell in behind and followed. Those on sidewalks and sitting and resting on benches stopped what they were doing and clapped and cheered. Shoppers and store clerks stepped outside and gawked and called out American Eclipse’s name, and workers in offices in buildings leaned out their windows and enthusiastically yelled out words of encouragement.

American Eclipse was their horse, and his legions of fans applauded and waved excitedly when he was swallowed by the passionate crowd as he continued his journey, no doubt in everyone’s mind to his date with destiny. That day would be May 27th, the day when the North and South would come together in what would turn out to be not only the first historically recorded match race but one of the greatest match races of all time.

Racing fans today often equate a racehorse’s success to the number of stakes wins on its resume. Money is important, of course, but that importance is generally only meaningful to the owners and trainers. When most fans evaluate the great horses of the past and the present, what is important to them are the number of Triple Crown race wins, Breeders Cup triumphs, and Graded Stake victories or their equivalents before the grading system came into effect.

If you search back in history and review American Eclipse’s record you will find that the great horse never competed in what we now call a stake race. The reason for this was because back in his day there were no stake races in North America, at least not until the Phoenix Stakes was run in Kentucky in 1831. There were only a handful of organized race meetings at the few courses that were in existence, and they were scattered around the country. These mini-meetings would usually last for just a few days, and they often attracted the better horses to compete against each other in races run in heats with two, three, and four miles as the most common distances.

In those early years of the eighteenth century, thoroughbred horse racing in America, even though it had been around since 1665, could still be considered in its infancy, and many horse owners and budding racing associations were endeavoring to make it grow. At the time, the sport was much more advanced in the South than in the North; in fact, the difference between the two was like the difference between day and night. There were many knowledgeable horsemen in the South, and they created an advanced breeding program that constantly bred foals that fed the sport, some of which eventually became stars. Furthermore, the South had already established a racing circuit, with the best courses being Newmarket in Petersburg, Virginia; the Central Course in Baltimore, Maryland; the Fairfield and Tree Hill courses in Richmond, Virginia; the Washington Course in Charleston, South Carolina; and the National Course in Washington, D.C. These were the ‘A’ courses, and they were typical of how we would best describe picturesque Saratoga Race Course in upper New York State today – remote and attracting many of the best horses and most successful horsemen.

There was also a secondary circuit, one where the lower-level horses and horsemen competed. This is where the smaller and often out-of-the-way ‘B’ courses were operated, such as those in Nottoway, Virginia; Lawrenceville, Georgia; and Lexington, Kentucky. Lacking the extravagance of the ‘A’ courses, which had clubhouses and covered grandstands and turf surfaces that were lush and well maintained, these ‘B’ courses had tiny stands with bench seating that stood in open areas without covers, and the horses raced over courses that were basically fields.

In a typical year, the southern racing circuit would begin in February in Charleston in what was historically called Race Week. Following Charleston, the circuit would move to Fairfield and Tree Hill, which were early spring meets, and then be followed in late spring by the Newmarket meeting, which back then was considered the nation’s top meet. The Baltimore and Washington meetings would be run in early summer, but before the horses moved there, they would compete at the only northern course that was included in the circuit, the new Union Course on Long Island, New York. Once the entire circuit was completed, it was repeated a second time in late summer and early fall.

With a well-organized racing circuit in place, those who were running the sport and the horse owners who bred and ran the horses that competed realized that stars must be established – those special horses that the public could identify with and hunger to see. With this mindset, the seeds that would blossom and flower into modern-day racing in the twentieth century were about to be planted. Large sums of money were invested, and many fine stallions and mares, some of them champions, were imported from Europe as America endeavored to improve the breed and develop its own champions.

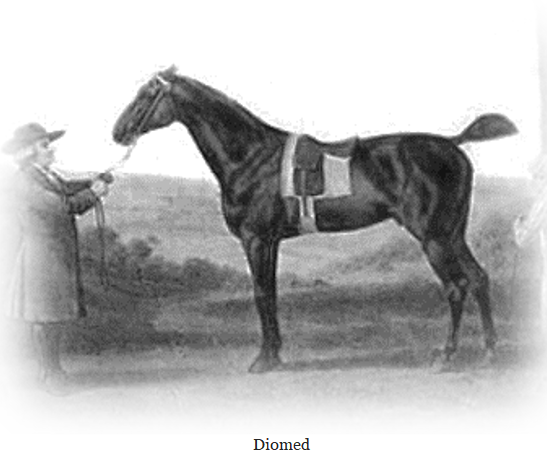

Diomed

One of these fine prospects was the English stallion Diomed, who was bred by Richard Vernon of Newmarket and sold to Sir Charles Bunbury, the president of the Jockey Club of England, for whom he raced. By Florizel, whose sire Herod was the greatest sire of his time, Diomed was out of the mare Sister to Juno, whose sire was Spectator, a successful racehorse and sire who was by three-time British leading sire, Crab.

Diomed stood for an initial stud fee of five guineas at Up Park Stud in Hampshire and later at Barton, in the district of Suffolk, England. The stallion had limited success, and in 1798, with his stud fee dropping to just two guineas from a previous high of ten, two pin-hookers, Messer’s Lamb and Younger, purchased the 21-year-old for fifty guineas. That spring, Colonel John Hoomes of Bowling Green and John Tayloe of Mount Airy, both those towns in Virginia, were looking to import stallions to America and expressed interest in Diomed, who many thought was too old for breeding purposes. Undaunted, they purchased him anyway for a rather steep price of about one thousand guineas and immediately shipped him to Virginia. As it turned out, any concerns that Diomed’s best days as a stallion might be behind him were quickly dashed. Success came immediately, and through his son, Sir Archy, Diomed would become one of the most influential sires in American history.

Diomed was a striking chestnut that stood 15.3 hands at his withers. He did not race as a two-year-old because Sir Charles Bunbury preferred to let his horses develop the strength and bone mass that was so necessary to be successful in British racing. Finally ready to begin his career in 1780, three-year-old Diomed’s first year of competition was highly successful as he won all seven of his starts, one of which was the initial running of the Epson Derby. Now considered a sensation, Diomed returned to competition when he was four and won his first three starts, which extended his undefeated record to ten and was considered by many to be the best racehorse since Eclipse, Britain’s immortal hero who won all eighteen of his starts a dozen years before.

Diomed did not taste the sting of defeat until he finished second to Fortitude in the Nottingham King’s Plate in his eleventh lifetime start. The unexpected loss was shocking, and after he lost his next race, he was taken out of training and remained inactive for the balance of the year. He returned to competition when he was five and was to face a grey colt named Crop but was declared before the race because he wasn’t physically right. When he failed to come around, for a second straight racing season he was taken out of training and once again remained out for the balance of the year.

Diomed was six when he was brought back to the races for one final season in 1783. In his first start, and in one of his most amazing efforts, he carried 168 pounds and defeated Lottery, a plate winner and one of the best horses of his time, in a race that consisted of three, four-mile heats. However, competing in such a difficult race after a lengthy layoff possibly had a deleterious effect because he never won another race and, after a string of six consecutive losses, was retired, finishing his career with eleven wins, four seconds, and three-thirds in nineteen lifetime starts.

While many people today consider Northern Dancer as possibly the most influential sire in the past fifty years, it is worth noting that Diomed was just as influential back in his day. His son, Sir Archy, was the grandsire of Boston, a great racehorse (40 wins in 45 starts), who was sired by Sir Archy’s son, Timolean, considered to be the best racehorse of his generation. Boston retired prematurely because of his failing sight (he eventually went blind in his final years) and gained even more fame at stud as he sired Lecomte and the immortal Lexington. A champion on the race track, Lexington was victorious in six of his seven lifetime starts, with his final victory coming in a much celebrated four-mile heat race against Lecomte in 1855 at the Union Course in New Orleans. His victory was seen as a measure of revenge, for it was Lecomte who handed Lexington his only career defeat in another grueling four-mile heat race the previous year.

With his sight also failing, Lexington was retired at age six and went on to have an illustrious career at stud. So proficient was he that nine of the first fifteen Travers Stakes winners were his sons and daughters, a fitting tribute for a great stallion who would be named the leading sire in North America in sixteen different years.

Because he was the sire of Sir Archy and the grandsire of Lexington, many great sires, broodmares, and racehorses trace back to Diomed. So profound is the Diomed line that today it is almost impossible to find any horse foaled in North America with early American bloodlines that does not have him in its pedigree, among them Northern Dancer, Native Dancer, Man o’ War, Sunday Silence, Cigar, Secretariat, American Pharoah……..the list goes on.

Duroc

American Eclipse’s sire, Duroc, who was only eight years older than his famous son, was bred by Wade Mosby and foaled in Powhatan County, Virginia, in 1806. Sired by Diomed, he was foaled by the Grey Diomed mare, Amanda, who was bred by John Broaddus a neighbor of Colonel John Hoomes. Mr. Hoomes, who was an agent for Broaddus, sold Amanda to Mosby for $300. The young filly was promising and won her first race by more than one hundred yards. Tragically, she pulled a tendon in her fourth race and was retired. Duroc was her first and only live foal as she was in foal a second time but was kicked by another horse and died, and the foal could not be saved.

Duroc was a big, muscular horse with a reputation for being temperamental and difficult to manage. One of his many idiosyncrasies was that he would often bolt in his races. In 1810, he was sold to Bela Badger of Bristol, Pennsylvania, for $2,500. Later that fall, he won a four-mile match race against another talented Diomed sired horse named Hampton in a time of 7m 53s, a new track record.

In 1813 Duroc was sold to Townsend Cock of Oyster Bay, Long Island, and was bred to fifty mares in his first season at stud. He was brought back to the races later that fall and won a four-mile heat race at Newmarket, defeating Pegasus and Volunteer. The following spring, after he completed his stud duties, Duroc made his final career start against Defiance and was leading the single-heat race when he bolted, a notorious habit of his, causing him to lose the race. He was retired from racing after that debacle and spent the rest of his life on Long Island.

Duroc is not listed among the great sires of his time, possibly because the small-scale breeding industry in New York was vastly different from the more vibrant industry in Virginia. Not many quality mares were sent to him, not like there would have been if he had remained in the South, and yet one of his foals would turn out to be the greatest racehorse of his time.

American Eclipse

Like many great horses that were previously mentioned as being descendants of Diomed, American Eclipse also traced back to this influential sire through his father, Duroc. Bred by General Nathaniel Coles and foaled on May 25, 1814, at his farm on Long Island, American Eclipse was out of the mare Miller’s Damsel, a grey daughter of the powerfully built grey-coated English-bred sire Messenger. Miller’s Damsel was what was called a first blood mare, meaning that she was by English-bred parents – Messenger and Sister To Timidity – but was foaled in America. Sister To Timidity was sired by Pot-8-o’s (sounds like potatoes), who in turn was sired by the great Eclipse, which meant that American Eclipse, who many considered the best racehorse in America, had blood from the best racehorse in England running through his veins.

Messenger was foaled at Oxford Stud at Balsham, Cambridgeshire, where his breeder, Lord Grosvenor, stood his stallions. Of particular interest was Messenger’s sire, Mambrino (also a grey), who was a descendant of Blaze. Blaze, who was also an extraordinary trotting sire, was sired by the talented Flying Childress, generally considered just below Eclipse in terms of quality, and a colt that easily won all six of his lifetime starts.

Messenger was imported to America in 1788 and joined two other imported sires, Medley (1784) and Shark (1786), the three to eventually be joined by Diomed in 1798. All would prove to be very instrumental as their breeders strived to develop quality racehorses that possessed the necessary speed and stamina that made racing in America very popular. But Messenger’s influence on the breed wasn’t just confined to thoroughbred racehorses. He also became one of the most influential sires of trotting horses in American Standardbred history.

Like her sire, Miller’s Damsel was a top racer during her career and was known as the Queen of the Northern Turf. Her copper-colored son, American Eclipse, was the second of her three reported foals, though her other two offspring, the fillies Sportsmistress and Young Damsel (both grey), reportedly raced, but their records were spotty and untraceable.

American Eclipse was a handsome foal with much promise and benefited because he was brought along slowly. Muscular at birth, he was unraced at two and trained for nine weeks at three before he made an unofficial start in a trial race. After winning it impressively and showing much promise he was turned out for the year and allowed to mature properly, a decision that was particularly important back then when horses often carried heavy weights and ran in lengthy heat races. He made his first official start the following year and defeated Black-Eyed Susan and Sea Gull in a series of three-mile heats for a purse of $300 at the Newmarket Race Course at Hempstead, New York. After that, he was turned out once again.

(NOTE: The Newmarket Course at Hempstead was established in 1665 and is considered America’s first official racecourse. However, it should not be confused with the Newmarket Course in Southern Virginia).

Early in his five-year-old season, American Eclipse was purchased for $3,000 by the reclusive Cornelius Van Ranst. A thin, grey-haired sixty-year-old, he had been involved in horse racing, first as a trainer and eventually as an owner, since he was a young teenager. Over the years, he had become so successful that he was often called the Old Wizard because of his uncanny ability to change a horse’s disposition and make him want to succeed. After spending some time with his new investment and confident that he was ready for competition, Van Ranst raced American Eclipse twice that year. The first time was in July when the powerful chestnut defeated a rugged challenger named Little John and two others in a series of four-mile heats. Eclipse’s second start was in October, and he showed that he was clearly superior as he defeated Little John once again, this time in a $500 race.

Undefeated after three lifetime starts and already well-known to northern horse racing enthusiasts, Van Ranst felt that American Eclipse had nothing left to prove against the weak competition in the North and decided to retire him to stud with his fee reported to be $12.50. Horse owners realized that American Eclipse would be a key sire in the North’s desire to improve the breed, and the great horse’s second season at stud saw him cover a whopping eighty-seven mares, which was significant because that year he was bred to more mares than many sires in America covered in a lifetime.

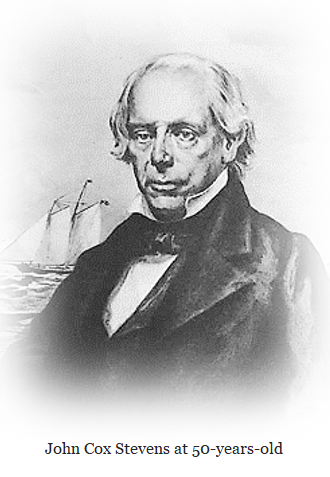

John Cox Stephens, who at the time was president of the Jockey Club, was a powerful and influential figure in New York and the northeastern seaboard. Born on September 24, 1785, at the family estate in Hoboken, New Jersey, he was a man of many talents. After graduating from Columbia University in 1803, and encouraged by the success of both his grandfather, John Stevens Jr., a well-known New Jersey politician, and his father, Colonel John Stevens, who was a revolutionary war hero and pioneer in the successful progress of steamboats, Stevens junior successfully managed the company that operated the first steam Ferry between Hoboken and New York City. At the time, he was also deeply engrossed in the sport of horseracing and was the current president of the Jockey Club, though his true passion lay in yachting, and in his later years, when his horseracing career had waned, he was honored as the first Commodore of the New York Yachting Club.

Yachting aside, it was Stevens’ love of horseracing that endeared him to the people of New York. He was a founding member of the Union Club, the City’s oldest gentlemen’s club, in which he became friends with some of the richest people in the city. Their financial backing, along with a large contribution from himself, allowed him to head a consortium that built a new state-of-the-art racetrack, which he named the Union Course. It was on a tract of land on Long Island, not far from the heart of the city, and, among other things, boasted the world’s first dirt surface. The consortium’s intention was to attract the best horses currently racing, which at that time meant established stars from the South, and what better way to encourage them to come than to have them challenge American Eclipse?

One of Stevens’ greatest attributes was his ability to persuade others to follow his lead in business matters. After much urging and as a favor to his friend, Van Ranst, who was also a member of the Jockey Club, decided to bring his champion out of retirement and enter him in a four-mile heat race on opening day, October 18th, for a purse of $500. With the race now confirmed, Van Ranst approached Samuel Purdy, reputed to be America’s greatest jockey, his continued success eventually earning him membership in the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame in 1970. Born in Westchester County, New York, in 1785, Purdy rode horses in the North and South and was often sought after because of his superior riding skills. Since Van Ranst took ownership of American Eclipse, Purdy had been the only jockey to ride him, and the horse and his rider had developed a special bond, a rare connection that was built on trust.

Having not raced in nearly two years, American Eclipse would face three challengers – Flag of Truce, Heart of Oak, and the outstanding mare, Lady Lightfoot, long one of the top horses in the South and considered so good that when the race went off, she and not American Eclipse, was the 2-1 betting favorite. For American Eclipse, who was now seven, the old competitive fire was still there, and he won the first heat by two lengths over Lady Lightfoot in 8m 4s while the others languished far behind.

A half hour later only American Eclipse and Lady Lightfoot remained to line up for the second heat as the other two challengers were scratched. Despite having lost the first heat, Lady Lightfoot’s backers were still confident. She was no pushover and had won more than thirty heat races in her career, many of them against the best horses in training. She also had a reputation for becoming stronger as the heats progressed, but despite her impeccable record and the confidence of her supporters, it was evident soon after the second heat got underway that she was no match for American Eclipse. The champion from the North showed that he was, without a doubt, the best horse in America, and he won the heat as he pleased. He also drew praise from the National Gazette, which reported that Lady Lightfoot was distanced.

Because his star performer’s form was so good, Van Ranst decided to keep American Eclipse in training and the following year entered him in three races, the most starts in any single season in the great horse’s career. His first race was on May 30th, 1822, in which he was to have a return match against Lady Lightfoot, the two being joined by another good southern horse named Sir Walter, a five-year-old who was owned by Bela Badger from Pennsylvania, the man who at one time owned American Eclipse’s sire Duroc. Though Sir Walter was owned by a northerner, the son of Sir Archy was considered more aligned to the South, and much like American Eclipse’s race against Lady Lightfoot, which had a North versus South flavor, so did this one. In fact, it would prove to be a catalyst in a not-so-friendly rivalry that was beginning to heat up.

Their first of two meetings was well publicized, even after Lady Lightfoot had declared, and betting between the Northerners and Southerners was brisk. American Eclipse and Sir Walter would run in a series of four-mile heats for a purse of $700, and as it turned out, the not-so-friendly rivalry would quickly escalate into a Southern obsession by the time the day was over.

The first heat wasn’t even close, and American Eclipse won it in a good time of 7m 54s. When the great horse won the second heat rather easily, his northern fans cheered loud and long and proclaimed him to be the greatest racehorse ever in America. This angered the Southerners, and they immediately demanded a rematch.

The two horses faced each other again in October, this time at the Union Course in a series of four-mile heats for a purse of $1,000. Joining Sir Walter in the challenge were two others, a filly named Duchess of Marlborough and the mare Slow and Easy. Lining up for the first heat, the southern horsemen were bragging, their hopes high. In less than eight minutes, American Eclipse not only wiped the smiles from their faces but also shattered their confidence. The circumference of the track was one mile, which meant that they would circle it four times, and Eclipse showed that he was up to the challenge. He led every lap and was an easy winner in 7m 59s with Duchess of Marlborough a surprising second.

In the second heat, only Sir Walter offered up a challenge as both Duchess of Marlborough and Slow and Easy were declared. The heat began without incident, but part way through, American Eclipse’s backers became nervous. As expected, the great horse led through the first lap though no one expected Sir Walter to push him so hard and be as close as he was. When Sir Walter suddenly went into the lead and managed to be a half-length in front after the second lap, there was a buzz in the crowd of fifteen thousand. This could not be. No horse had ever led American Eclipse at this point in a race, and suddenly buoyed with confidence, the Southerners began to celebrate. A great victory was certainly within their grasp, and with it, the record would finally be straight……..Northern racing might be improving, but Southern racing was still far and away more superior.

It was then, when the bragging and jabbering were at their most intense that the Southerners would see just how good American Eclipse really was. With Sir Walter’s challenge creating a loud cheer as it lifted all those southern hopes, the great champion, as proud as he was dominating, suddenly reacted, and the predominantly northern crowd exploded with a loud roar as he rushed past his overmatched challenger and spurted into the lead. From that point on, American Eclipse opened up and lengthened the distance between the two. Finally having enough, and to the disgust of his southern backers, Sir Walter quit, and American Eclipse cantered home an easy victor.

The string of three straight losses to American Eclipse left a sour taste that was too much for southern horsemen and fans to handle. They would challenge this upstart from the North yet again, and this time, they would put him in his place once and for all. The challenge they issued was for a race to be run on November 20th at the National Course in Washington against James J. Harrison’s Sir Charles, a Virginia-bred son of Sir Archy, who was reputed to be the swiftest horse in the South. Each side would put up a sum of $10,000, and they would run four-mile heats.

Without hesitation, Van Ranst, with urging from Stevens, accepted.

Sir Charles

In his day, Sir Charles was considered one of the best sons of Sir Archy, along with another famous son, Bertrand, who was foaled in 1820. Both had impeccable track records, as Bertrand won thirteen of fifteen starts, six of them in four-mile heats and four others in three-mile heats.

Sir Charles, who was owned and bred by Harrison, was foaled in 1816 at his plantation called “Diamond Grove” on the Meherrin River in Brunswick County, Virginia. Hailed as the champion of Virginia, Sir Charles had started twenty-five times (his race against American Eclipse would be his twenty-sixth start) and won twenty of them while finishing second four times. He was very versatile, with four of his victories coming in four-mile heats, four in three-mile heats, and six in two-mile heats, while the distances of his other six victories were not recorded. He was at the pinnacle of his career when Harrison issued the challenge and was thought to be an extremely worthy challenger to American Eclipse, definitely a horse that the South would rally around.

The race organizers believed that this race was shaping up to be one of the best ever, and they wanted the public to embrace it. In an effort to drum up even more publicity, for the first time, a race featuring American Eclipse was heralded as a battle between the North and the South instead of the traditional horse versus horse. The New York Daily Advertiser supported this claim and wrote that this race would create much interest – “It is the North against the South,” it proclaimed and in one of its columns stated: “When Greek meets Greek, then comes the tug of war.”

True to form, racing fans embraced the rivalry and were eagerly looking forward to it, with many confident fans, all of whom were looking for revenge, making their way up from the southern states. However, as the big day neared, to their dismay Sir Charles suffered a tendon injury while training and came up lame. James Harrison decided to declare him, which resulted in the forfeiture of half of his $10,000 stake. Although many southern fans became outraged with the decision, Harrison was looking out for their interests as well as those of his horse. By declaring Sir Charles, he preserved the betting integrity of the race as more than $100,000 was bet on it, and it wouldn’t be fair to the backers of Sir Charles to risk their money on a four-mile heat race when he was not one-hundred percent fit.

With fans from the South visibly upset at having traveled all that way to Washington only to have the race canceled, Harrison agreed to put up $1,500 and have Sir Charles and American Eclipse run that same day in a single heat at four miles. Members of the Washington Jockey Club, after having Sir Charles thoroughly examined and declared fit to run, sanctioned the race. They reasoned that the horse appeared healthy enough to run four miles, but the stress of running eight or more miles was too risky.

Interest in the race was paramount, drawing many politicians and dignitaries, including President James Monroe and his Secretary of War, John Calhoun, who were seated in a private booth. Both were from Virginia and being Southerners, it was only natural that they would cheer for Sir Charles. It is not known if they wagered on the race, but many other fans did, and in no time, thousands of dollars were risked by confident braggers from the South.

It would later be written that Sir Charles put up an admiral challenge against the best horse in the world and gallantly chased him through a very fast opening lap in 1m 55s. Reports further stated that at this point, the southern challenger began to fall back, and one lap later, when he was considered double-distanced, he was pulled up, and Eclipse went on to win the heat in a leisurely 8m 3s.

After the race, Harrison was distraught. By bending to the pressure and racing Sir Charles when he was obviously in an iffy condition, he not only lost an additional $1,500 but also lost his horse, as Sir Charles, whom many considered the best in the South, would never race again.

As Van Ranst stood in the winner’s circle with his champion, who was now undefeated in seven career starts and was undoubtedly the most celebrated and famous racehorse in North America, his thoughts were of retirement and a life at stud. No doubt his majestic warrior had earned it, but before the day was over there was word that the South wanted yet another challenge, and two days later, while Van Ranst was still savoring the thrill of victory, one was formally put forth.

The South had now lost four consecutive races to American Eclipse, all with their best horses. Maybe it was because of his petulance, which had built to an intolerable level because a northern horse, of all things, was considered the best racehorse in the country, but William Ransom Johnson, the most renowned horseman in the South and probably in all of America, was not about to accept this situation without a fight. In his mind, Southern racing was far more sophisticated and better organized than what was being conducted in the North. It was also a well-accepted fact that the South had the best horses. He aimed to keep it that way, and backed by several prominent horsemen, he issued a formal challenge whereby the South would risk $20,000 to prove it.

John Cox Stevens found this challenge too much to ignore. It was true that American Eclipse would soon be nine and possibly wasn’t quite the horse he once was, but he was still in marvelous condition and had never had a physical problem in his life. Nor had he ever been seriously tested when dispatching the best that the South had to offer and, in doing so, had dominated his races with ridiculous ease. And being John Cox Stevens, a leader of men, he had no problem getting several rich members of the Union Club to contribute a share, along with himself and Van Ranst, in the $20,000 stake.

And so, the challenge was accepted and the guidelines for what would forever be called the Great Race were set. American Eclipse would face an as-yet-to-be-named challenger from the South, said opponent need not be named until the race’s post time, in a four-mile, best-of-three-heat race, for a purse of $40,000 with each side putting up half. It would be held the following May at the Union Course on Long Island and would be governed by the Union Course’s rules, including its Scale of Weights. To ensure the integrity of the race, each side was required to put up a $3,000 forfeiture bond if one of the sides decided to back out, the money to be deposited in a local bank.