1984 Breeders' Cup

Hollywood Park

November 10, 1984

By: Walter Lazary /// November, 2024 /// 4,451 Words

John Gaines Photo - Breeders' Cup

A Dream Come True

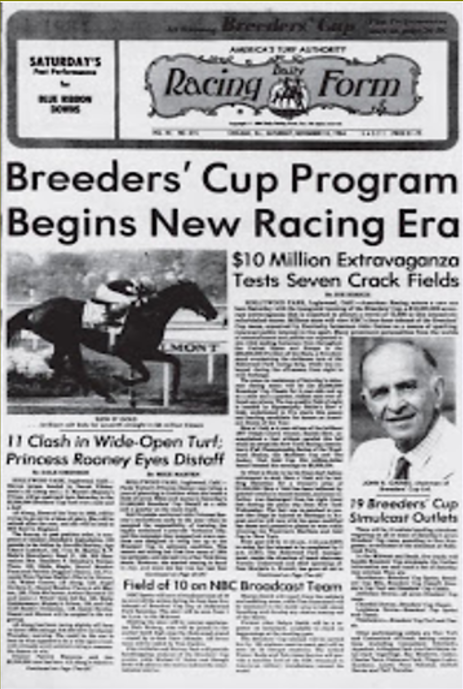

The inaugural Breeders’ Cup was held on November 10, 1984, at Hollywood Park in sunny California. Only sixty-eight horses competed in the seven races in this highly anticipated event, but for the on-site crowd of 64,254, plus millions more watching on television, there was no shortage of talent.

Of the nine possible American Eclipse Award winners that year (excluding the award for the best steeplechase horse), six of them competed on this historic card: Chief’s Crown (2-year old colt); Outstandingly (2-year-old filly); Life’s Magic (3-year-old filly); Slew o’ Gold (older horse); Princess Rooney (older mare); Eillo (sprinter). And if John Henry, eventually to be voted the country’s top turf horse, as well as Horse of the Year, hadn’t been declared from the Breeders’ Cup Turf because of a career-ending leg injury, it would have totaled eight, quite possibly the first time ever in the long history of the sport that so many year-end divisional and HOY winners competed on the same card. In fact, besides John Henry, the only horse to win an Eclipse Award that did not race that afternoon was the Kentucky Derby winner and eventual three-year-old colt champion, Swale, who tragically died just a few days after winning the Belmont Stakes.

That first Breeders’ Cup was pulled off without a hitch, and it showed the world that a sport, which was governed by so many independent groups, could actually come together and put on a grand show that did the industry proud. But was that really the case?

For those who are new to the sport, in the two years leading up to this event, it might be difficult to comprehend the controversy, bitterness, and downright animosity that raged back and forth between some of racing’s most distinguished and well-respected individuals. There were many who supported what they considered as being a brilliant concept that would revitalize the racing industry, and yet there was also a large group that was definitely opposed to this series of races that, in one way or another, would change the landscape of North American horseracing forever.

When looking back, the Breeders’ Cup has been a much-needed shot in the arm for a sport that was struggling at times; and over the years, one wonders if it has been the inspiration for other major events such as the Dubai World Cup and the recent Saudi World Cup. These two Middle East extravagances have definitely encouraged international participation, which no doubt has been aided by their locations. And their major races offer purses that are far greater than what the Breeders’ Cup currently offers, but that is because their purse money is put up by their racing associations, while the Breeders’ Cup garners its prize money from fees paid by horse people within the industry with only a percentage of the actual fees collected being allocated to the Breeders’ Cup purses, while a large percentage is given back to the industry, mainly to various race tracks to help increase the size of their purses.

John R. Gaines

The Breeders’ Cup began as a novel idea put forth by John R. Gaines, a prominent thoroughbred racehorse breeder whose father once owned the Gaines Dog Food Company before selling it off to General Foods. Mr. Gaines was a visionary and explained that one way for racing to keep up with the growth of the country’s major sports, while also competing with other forms of gambling was to have a championship day of racing, a special day when all age groups would be recognized on both dirt and turf surfaces and would entice some of the top horses in the world to come and participate.

Mr. Gaines, who owned one of the world’s foremost breeding farms and at the time stood such prominent stallions as Lyphard, Blushing Groom, Irish River, Riverman, and Vaguely Noble, put forth his idea to some of the most powerful and influential people in the sport when making a speech at the 1982 Kentucky Derby Festival. As far as he was concerned, after the successful decade of the seventies, a magical ten years in which there were three Triple Crown winners, the sheer brilliance of arguably racing’s greatest ever filly Ruffian, and exceptional performances from other superstars such as Forego, Alydar and Spectacular Bid, racing had hit a lull. Sure, the reformed claimer, John Henry, was exciting fans across the country, and in 1980 Genuine Risk became just the second filly to win the Kentucky Derby, but that was it. Nothing else that would draw new fans to the sport as well as retain the current ones really stood out.

In 1982, people within the industry and racing fans, in general, were angry when trainer Henry Clark and owner Jane du Pont Lunger decided to skip the Kentucky Derby with the early favorite Linkage and point their colt to the Preakness Stakes instead. In American horseracing, this was considered sacrilegious, and the outrage that followed saw Clark called a number of things, among them being incompetent, disrespectful, and even a Kentucky Derby hater. In Linkage’s absence, America’s greatest race was eventually won by 21-1 shot Gato Del Sol, but this eventually led to even greater outrage when that colt became the first Kentucky Derby winner in 23 years to skip the Preakness and prepare for the Belmont Stakes. This rankled racing fans to no end, many of whom, including the executive vice president and general manager of Pimlico Race Course, Chic Lang, voiced their displeasure and accused trainer Eddie Gregson and co-owners Arthur Hancock III and Leone Peters of cowardice and failing to support the crown-jewel of American horse racing, the Triple Crown. Then to top it off, both Linkage and Gato Del Sol, as well as the Preakness winner, Aloma’s Ruler, were absolutely destroyed in the Belmont Stakes by Conquistador Cielo, a horse that would have been good enough to win the Triple Crown except that he missed the first two legs while he recovered from a minor leg injury.

Racing fans, those who were really interested in the sport and eagerly anticipated racing’s biggest series, the Triple Crown, were extremely upset. Many considered these failures to compete an insult to the sport, and this was a major concern.

In truth, those who were running the sport had been stubbing their toes in recent years while horseracing was losing fans as well as its credibility. Mr. Gaines did not like what he was seeing, and he believed that if racing was going to survive and gain new fans, it was imperative that it be more interesting for the average two-dollar bettor, that they must encourage them to be just as much or even more interested in the horses themselves, and not just the stars, than the actual gambling.

“The two-dollar bettor is the person we must reach,” Gaines said. “An event such as this might help him or her to become a true racing fan and encourage them to attend the races to see the horses instead of going to the stock car races or other sporting events.”

Mr. Gaines went on to make other points. “The success of the inaugural Arlington Million last August (1981) is a clear indication that owners and breeders in the United States are extremely interested in high-quality stakes races for big purses. The Breeders’ Cup, if it materializes, could be a grand day of racing, and just as champions are crowned in other sports, the thoroughbreds crown their champions too. This event could help build momentum and be a fitting preliminary to the Eclipse Award balloting, and what better way to determine the champions than head-to-head meetings on the racetrack?”

Gaines then went on to explain his vision: seven championship races with a minimal purse of $1 million and a maximum of $4 million. The card would be rounded out with two $250,000 races for horses not participating in the actual Breeders’ Cup races but be openers on the same card, plus a steeplechase race, the total purse money totaling $13.5 million.

When asked where the money would come from, Gaines stated that they could implement a system that was not unlike that used in quarter horse racing where the horsemen and not the tracks would put up the money. Horsemen could nominate the progeny of participating sires, those sires to be made eligible at a cost equivalent to the advertised stud fee for each plus an additional amount if the stallion has more than fifty foals in a given year, this due on an annual basis. In Europe, the nomination fee would be 50% of their fee, and in South America, 25%. The breeders of the resultant foals would also pay a one-time nomination fee (the amount to be determined). In addition, there would be declaration, entry, and starting fees as well as revenue from a TV contract, which he estimated to be approximately $2 million.

When asked why he envisioned this event in the fall when professional and college football dominated, he was very explicit: “This time of year was selected so we will have an anchor at the end of the racing season. We would have a goal for all at the end of the year and that would be a series of championship races. Obviously, if you put forth a program worth millions of dollars in purse money, people are going to be interested, and owners and trainers are going to point their horses for this just like they would point them to any other major race.”

On the surface, this was a wonderful idea, but like all wonderful ideas, there was a downside. Many people were skeptical that such an idea would work, at least past the first year or so, while others complained that a series like this would negatively impact other important fall races.

The New York Racing Association (NYRA) was particularly upset because it felt that it currently presented a series of championship races in the fall: The Futurity, Frizette, Champagne, Beldame, and the latest version of the New York Handicap Triple, the Woodward, Marlboro Cup, and the Jockey Club Gold Cup, as well as top turf races like the Man o’ War and the Turf Classic. In addition, Laurel held the annual Washington D.C. International on turf, which would surely suffer, and Woodbine would see interest in its Rothman’s International drop as top International horses would avoid it because it was too close to the Breeders’ Cup. Some also pointed out the fact that the Rothmans, along with the Turf Classic and the D.C. International, already presented a good three-race series for turf horses, both local as well as those from overseas.

John Shapiro, the president of Laurel Race Course, was particularly incensed and fired off a letter to Mr. Gaines that read: “I am very much opposed to your concept. It will hurt Laurel Race Course more than any other track in America because of the time that it is run, and it will be in serious conflict with the Washington D.C. International, a traditional event that has taken years to build up.”

The connections at Arlington Park, which offered the world’s first million-dollar thoroughbred horse race, were more supportive. They maintained that the Arlington Million wouldn’t be overly affected as their race was held in late August and would attract European horses who could stay and compete in the Breeders’ Cup. However, other mid-west venues sang a different tune.

Seth Hancock, who ran Claiborne Farm, was concerned about Kentucky racing, especially the lucrative Keeneland fall program. He stressed that nothing should greatly disturb the sport in Kentucky with its incomparable racing assets. It has the Derby and the bluegrass region, which produces the world’s best thoroughbreds, and it has Keeneland, a delightful track that proves that good racing can flourish in a traditional setting surrounded by America’s finest horse farms without blatant commercialism.

“It would kill the Breeders’ Futurity and the Alcibiades,” Hancock said. “As well as the Spinster, which is a major race that annually helps determine filly and mare champions. These and other races have stood the test of time. People have put their life’s work into building them up to what they are now.”

Nevertheless, despite these concerns, and there were many others, there were a greater number of positives, and in the end, the positives won. A short time later, in July 1982, the Breeders’ Cup Ltd., a non-profit organization, was formed with John R. Gaines, who owned Gainesway Farm, named as president, with Brownell Combs II of Spendthrift Farm, and Seth Hancock III of Claiborne Farm, named as vice-presidents. One of their first duties was to appoint Will Farish III (Lanes End Farm) to chair a committee to seek out other board members who would be charged with devising a workable plan for the initial Breeders’ Cup. Among these were Bert Firestone (Catoctin Stud, Virginia and Gilltown Stud, Ireland), Nelson Bunker Hunt (prominent breeder in Lexington), Brereton C. Jones (Airdrie Stud), John Maybee (Golden Eagle Farm), John Nerud (Tartan Farm), and Charles Taylor (Windfields Farm).

Even though progress had been made, it still did not mean that everyone was satisfied. There would be several new squabbles, the foremost of which was where to hold the inaugural edition, which was slated for 1984. Eight racetracks immediately submitted their applications: Belmont Park, Hollywood Park, Santa Anita, The Meadowlands, Arlington Park, Woodbine Racetrack, Atlantic City, and Hawthorne Park. President Gerald McKeon of NYRA, when submitting his application, came right to the point and gave the committee an ultimatum: “We are willing to shift our fall race meetings in order to obtain the Breeders Cup Series. Give us this event for the first three years that you hold it, or we’re not interested, period.”

McKeon then added: “We have the most to lose by not getting it. Historically, all the divisional championships have been won and lost in New York. I think that Ack Ack was the only horse to ever win Horse of the Year without racing in New York in the year that he won it (Ack Ack actually began his career as a two-year-old in New York). Perrault (currently one of the country’s top horses) is running in the Marlboro Cup today because his owners and trainer know that a horse must still win a major New York race to be named Horse of the Year. But by 1984, if the inaugural Breeders’ Cup is on the West Coast, horses like Perrault and John Henry could still win the title while racing exclusively in California. Championship races like the Marlboro Cup and the Woodward would then become mere tune-ups for the Breeders’ Cup.”

Dave Stevenson, director of racing at NYRA, put forth the argument that he believed that Belmont Park was the ideal location to hold such a large event. “It’s suitable for large fields and is the only racetrack in America to have a 1-1/2 mile main track. And it certainly can handle large crowds. It is the most logical place to hold these races.”

Stevenson could see the Cup series, involving rich races in each of the various divisions, as fitting in perfectly with the other races already run at the Belmont meeting, known as the Championship Meeting, because all of the divisional titles are usually decided there. “It coincides exactly with our fall schedule of big races, and it dovetails perfectly with those races.”

West Coast vs East Coast

In September 1982, the Breeders’ Cup made a decision that rocked the boat when it awarded the inaugural event to a West Coast track, either Hollywood Park or Santa Anita. They further announced that the Breeders’ Cup would shift east for the 1985 edition, with either Belmont Park or Monmouth Park to be the desired locations. This did not go over well with NYRA’s officials, who were miffed that their threat to pull out if they were not awarded the inaugural Breeders’ Cup was ignored. What was particularly disturbing was the fact that Belmont Park was not even assured that it would get the second edition.

The Breeders’ Cup committee cited two reasons for deciding on the West Coast: the favorable weather conditions at that time of year in Southern California as opposed to the East Coast and/or the Mid-West; and a possible rift within NYRA as some of their officials insisted that the Cup would interfere with their fall racing schedule, while others weren’t overly concerned and openly lobbied to hold the event.

With the location for that first year basically settled, there were still other issues that jeopardized the event, and they came to a head in late September. That was when prominent breeders Seth Hancock, Brereton Jones, and William duPont III resigned from the Breeders’ Cup board of directors, all citing the fact that they did not like Mr. Gaines’s format whereby so many across the industry would put up the money that in the end only a relative few could win. They also did not like the fact that they could not change Mr. Gaines’s mind on this and several other issues and accused him of running the show without seeking much council from his board.

In addition to the three resignations, reports flourished throughout Kentucky that more of the board members might withdraw. What these board members wanted was for the purse money, which at times was estimated to be as high as $18 million and had currently been reduced to $13.5million, to be reduced even more with the balance of the fee money collected to be redistributed to race tracks, to help increase their purse structures, as well as to farms and breeders in general.

And there were several other issues that had to be ironed out. One was the annual nomination fee required for participating stallions. Many stated that it was unfair that a stallion like Northern Dancer, whose fee was $1 million, and other stallions, whose fees were in the $250,000 range, were required to pay such hefty amounts compared to stallions who were in the $5,000 to $10,000 range and yet have their progeny all race for the same purse money. But as much as this discrepancy was a concern, what really rankled Hancock and the others was their charge that Gaines was operating as a one-man decision-maker without accepting input from others, a concern shared by many.

In support, Brereton Jones stated categorically that the program was dead. “You can’t get a few people in a room to force something on an industry like racing. It is unhealthy to collect all this money from thousands of people in our industry and give nearly 75 percent of it to a handful of people in one day. For example, you are not going to get people in Maryland to nominate their horses and their stallions and pay a lot of money to be eligible and then have their horses compete against the sport’s heavyweights. The odds are against these smaller people anyway, so why should they put up their money?”

These concerns were aired out in September. On October 20, at a board meeting that was called in a last-ditch effort to save the event, Mr. Gaines, who realized that for the Breeders’ Cup to continue, he must step aside, put forth his resignation. It was accepted, and in a unanimous decision, prominent Lexington attorney, Gibson Downing, himself a racehorse owner, was chosen to replace him on an interim basis. In Downing’s first act of business, he said that he would appoint a committee to find replacements for Mr. Gaines, as well as John R. Hardy, who was the executive director, and who had also resigned. In a compromise, Mr. Gaines would stay on as chairman of the board but would not be involved in the daily affairs.

From there, real progress was made. Apart from Mr. duPont, those who had originally resigned rejoined the group and were involved in changing the annual nomination fees for foals, though the original stallion nomination fees would remain the same. In June 1983, the seven-race format was also changed. The total purse money was reduced to $10 million and would be allocated as follows: the Juvenile Colt and Gelding, Juvenile Filly, the Sprint, the Mile, and the Distaff purse offerings would be $1 million each, the Turf would be set at $2 million, and the Classic set at $3 million. This format would give all horses of different ages a chance to participate, would still encourage international competition, and would allow them to allocate an additional $3.5 million to horsemen and racetracks.

********

One thing in the industry that has remained constant over the years is that there always seems to be some sort of controversy. And for that first Breeders’ Cup, there would be a lot of it – and if you were on the outside looking, you would surely think that something wasn’t kosher.

It began in February 1983, when Hollywood Park was awarded the first Breeders’ Cup, the date to be November 10, 1984, and not on the last Saturday in October, which had been initially planned. The Breeders’ Cup board of directors, voting on a recommendation put forth by a four-man committee that also considered a presentation to hold the event from the Oak Tree Racing Association at Santa Anita, decided that Hollywood Park would be chosen, without disclosing a breakdown of the eighteen votes that had been cast.

“Both Hollywood and Oak Tree made strong and enthusiastic presentations,” Nelson Bunker Hunt, a member of the screening committee, said. “This was the most difficult decision I’ve ever had to make in racing.”

Marge Everett, the chief operating officer at Hollywood Park, was ecstatic. “I am thrilled, thrilled, thrilled that we’ve been selected to host the event,” she said. “In fact, this is the most thrilling day I’ve had in my 42 years in racing.”

Herman Smith, executive vice president of Oak Tree, declined to comment on the decision but later issued a statement. “Our first response is one of disappointment. But the important thing is that this great series will begin on the West Coast and thus serve to recognize the increased importance of Western Racing.”

An inside source that was privy to the actual decision would later say that Hollywood’s racing dates were more compatible than Oak Tree’s, which, if it had been chosen, would have been in direct conflict with a number of important stakes races run throughout the country.”

Others weren’t so sure, and their doubt would be confirmed a short time later when Marge Everett confirmed that she had made a $200,000 personal contribution to the Breeders’ Cup and that the money was promised before the final decision had been rendered. “I don’t want to be maligned for this,” she said. “There is nothing sinister about it. I would be terribly upset if it resulted in a blemish because my motives are philanthropical and charitable.”

A high-ranking Santa Anita official, who asked that his name not be used, said: “This is something. Here we thought the decision had been made based strictly on our presentations.”

In his response, Gibson Downing, the interim president of the Breeders’ Cup Ltd., said, “I am not uncomfortable with Mrs. Everett making a contribution of this sort. I was not on the selection committee, but I am sure that her gesture had nothing to do with the selection of Hollywood Park. The key to selecting Hollywood was its apparent ability to make this a big media event, including extensive coverage by the major networks. These people are connected with Hollywood Park, honorable people such as Howard Koch and Aaron Spelling, who will be most helpful in major coverage.”

Eventually, the controversy died down, though for most it would take time, while others were still bothered by it. But the show must go on, and so finally, with everyone in agreement, the Breeders’ Cup, to be held at Hollywood Park on November 10, 1984, was now officially confirmed, though there was still one last major hurdle, and that was a television contract. In September 1983, NBC came through in the form of a five-year contract. In return, the network would televise the entire event beginning at 2:00 p.m. EST. thru to its conclusion at 6:00 p.m.

“This is truly a landmark acquisition for our network,” said Arthur Wilson, president of NBC Sports. “We are extremely confident that “Super Saturday – The Championship Series” will immediately be recognized as one of sports television’s biggest attractions.”

From that point on, things appeared to be running smoothly, though there was still a hint of politics involved. In 1984 another $5,910,000 would be allocated to increase purses for 189 stakes at 28 different racetracks. It could be argued that in an effort to appease NYRA and keep New York interested in participating in future Breeders’ Cups, $1,700,000 (29%) of this amount was ear-marked for 46 stakes at Saratoga, Belmont Park, and Aqueduct, which was in stark contrast to the New Jersey tracks, Atlantic City, Monmouth Park, and The Meadowlands, which received $623,000 (11%) for their entire stakes’ programs. But who could argue? The new format was much more beneficial to the racetracks and horse people in general than the original one put forth by Mr. Gaines, and it was widely supported.

And so finally, after seventeen months of doubt, criticism, and animosity from many quarters, and fear that it would detract from many of the country’s most important stakes, including the Triple Crown, the Breeders’ Cup was a go. John Gaines’s novel concept had not only managed to stay afloat, but it also became so popular that it won nominations from every major thoroughbred breeder in the country and a host of minor breeders as well.

Despite its success, however, one of the initial fears when the Breeders’ Cup was created never came to fruition. The event is still second in popularity to America’s Triple Crown, and that seems to be fine with true racing fans throughout the land.

The Inaugural Breeders' Cup

As Marge Everett had promised, the inaugural Breeders’ Cup turned out to be a glamorous day of racing that drew fans from many parts of the country and from around the world. With a total of ten million dollars in purse money up for grabs, we were treated to an action-packed afternoon that featured two disqualifications, a turf course track and American record, and an improbable winner of this historic day’s biggest race, the $3,000,000 Classic.

Please tap on the appropriate link below for an in-depth analysis of each of the seven Breeders’ Cup races, including videos, charts, and photos.